Due to the impact of the novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19), many art exhibitions are now being held online. This series of articles is devoted to exploring the possibilities of online art exhibitions, which are now being tried out in various forms. In this article, we divide online art exhibitions roughly into three trends and look back on the major exhibitions held from the end of 2019 through 2021.

From the web-based exhibition DOMANI plus Online 2020: Living on the Eve

From the web-based exhibition DOMANI plus Online 2020: Living on the Eve

The only true voyage of discovery, the only fountain of Eternal Youth, would be not to visit strange lands but to possess other eyes, to behold the universe through the eyes of another, of a hundred others, to behold the hundred universes that each of them beholds, that each of them is...”

—Marcel PROUST, Remembrance of Things Past (*1)“It’s true, isn’t it?” “Not always. The future can change steadily on the spur of the moment.”

—FUJIKO F. Fujio, Doraemon (*2)

Three factors to consider about online exhibitions

“Online art exhibitions” (hereinafter referred to as “online exhibitions”) in a digital environment, have been attempted in various venues since the 1990s when the Internet first became popular (*3). The history of these events has continued in parallel with the development of computer networks, but in this article, I would like to consider the subject of online exhibitions since the start of the novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic. In some areas, such as online conferences and webinars, the technology and practices have been in place for a considerable time, but their application has evolved and become more widespread out of necessity during the pandemic, and the same can fairly be said about online exhibitions. In Japan, in parallel with the social impact of COVID-19, I believe that the following three major developments have taken place.

1. Real space exhibitions have moved online.

2. Unique online exhibitions have been held.

3. Coordination has been achieved between real space and online space.

Of course, these three elements can be mixed within a single practice, and while their order of implementation may not be completely linear, I think they make good indicators for the purpose of considering online exhibitions. In the following sections, I would like to take a closer look at some examples of all three of these elements.

1. Taking real space exhibitions online

Perhaps the biggest and most urgent challenge that the COVID-19 pandemic has brought to art institutions has been the cancellation and postponement of exhibitions. In Japan, from the end of February 2020, national museums and art galleries decided in rapid succession to temporarily close their doors, and in this, they were soon followed by public and private museums and galleries in urban areas. This situation led to the growth of a movement to take 3D spatial photographs of exhibition sites after completing an exhibition setup and to release them to the public.

The exhibition Future and the Arts: AI, Robotics, Cities, Life – How Humanity Will Live Tomorrow, held at the Mori Art Museum in Tokyo, opened in November 2019 but ended almost a month earlier than originally planned due to a decision to temporarily close the museum from February 29, 2020. Before the removal of the exhibition, the museum carried out a photo shoot using the 3D virtual tour platform Matterport, and from May 1, some of exhibition’s contents including images from the photo shoot were released for viewing on the Mori Art Museum’s newly established online program MAM Digital. Opening during the Golden Week spring holiday period in Tokyo, where a state of emergency had been declared, this virtual tour attracted online visitors from all over the world, even while the museum itself remained closed to the public.

Matterport is a service provided by the U.S. company of the same name that allows people to create and publish 3D virtual tours by taking photos of real spaces using a dedicated camera. Then, in the Google Street View-like Walkthrough mode (which resembles taking a virtual gallery tour on Google Arts & Culture), users can enjoy a virtual walk around the 4K-quality 360-degree panoramic space. Supplementary information can also be added to various parts of the space, and texts and videos can be displayed by clicking on them. In addition, the interface is ingenious, complete with functions such as Dollhouse to provide three-dimensional overviews of entire target spaces, Floor Plan that allows users to create accurate floor plans, and Highlight Reel for making lists of key points. Matterport is being used in a wide variety of fields, from real estate sales to the recording of historical buildings. In Japan, it had previously been introduced by some art galleries (*4), but since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic it has been adopted widely by museums and art galleries throughout the country.

In some cases, 3D views of current exhibitions have been made available to the public. A notable example was the solo exhibition Tokyo TOKYO/MIKA NINAGAWA held at PARCO MUSEUM TOKYO in Shibuya in June 2020, and in this case, the primary aim may have been to use the online exhibition as a springboard for attracting people to visit the actual venue. Then in September of the same year, for the 23rd Japan Media Arts Festival Exhibition of Award-winning Works held at Miraikan – The National Museum of Emerging Science and Innovation and elsewhere, in addition to taking measures to prevent the spread of infections by requiring advance reservations and limiting the number of visitors, the organizers released a 3D VR version of the venue on a special website. The website was open for about a month after the closing of the onsite exhibition, showing the operational cooperation with the actual venue where measures to prevent the new coronavirus infection are required.

Of course, this type of online exhibition cannot be a perfect digital twin of a real venue. Not only is there the issue of lack of realism, but it is also difficult to achieve mutual interference between the work and the audience, which is possible in real space. (In this context, think of one of the artworks by Félix GONZÁLEZ-TORRES, where audience members were invited to take home pieces of candy from the work in front of them.) Or, as in the case of Tania BRUGUERA’s work in which the audience enters a room filled with menthol (tear-inducing vapor), the online experience of expressions that target senses other than hearing and sight is unlikely to be able to substitute for the real thing in the current general computer environment. Moreover, 3D views may not be an optimal solution for every art exhibition. For example, in the case of a painting exhibition held in a white cubic space, it may be possible to enhance an exhibition by simply displaying images of the works in a browser and then adding related texts and videos (*5).

On the other hand, I think this type of online exhibition, which records real space, has shown its potential for use as an exhibition archive. In addition to conventional media such as drawings, photographs and videos, online exhibitions could form a part of the “record” including of the exhibition design. (Incidentally, Matterport’s spatial recording also uses an infrared sensor, and by selecting the Measurement mode during the Walkthrough display, the user can display the distance between any two points.) In addition, online exhibitions look set to be used on a wide scale in future as a medium for presenting permanent exhibitions and individual collections of artworks (*6).

Online gallery talks, in which planners talk to viewers from the actual venue, have also become popular during the COVID-19 pandemic. Now that I think about it, the NHK TV program Sunday Art Museum has often featured noteworthy exhibitions from around the world as if they were on-air rather than online exhibitions, and attempts have also been made using the Internet, such as Nico Nico Art Museum, which has been broadcast on the Nico Nico live streaming site since 2012. Under the COVID-19 pandemic, online gallery talks have been tried out as independent projects for exhibitions in various places (although these projects have varied widely in terms of both their scale and contents). In the area of art festivals, Yamagata Biennale 2020 Shape of Mountains, Shape of Life was the first to be held online centered on video distribution, and SIAF2020 Document was a memorable online presentation showcasing a variety of the planned projects that were shelved after it was decided to cancel the Sapporo International Art Festival 2020. We will be watching closely to see whether these efforts to respond to the emergency situation in which the holding of physical exhibitions has been suspended will eventually lead to an essential expansion of “what can be done online.”

2. Unique online exhibitions

In keeping with the closure of art museums and other facilities from the end of February 2020, and the declaration of the first state of emergency in April, some art exhibitions that were about to open had to be cancelled or postponed. These circumstances gave rise to the creation of virtual exhibitions that envisioned the Internet as a “venue” from the outset. Among them were online exhibitions planned by the artists themselves, as well as projects put into practice by cultural institutions that lacked their own exhibition facilities.

At the end of March 2020, videographer SASAKI Yusuke and artist ARAKI Yu produced and held the online video festival Films From Nowhere (co-sponsored by Kannai Bunko, an art exhibition and information archive space operating in Yokohama). The works of nine artists, including their own, were distributed via the on-demand feature of the video platform Vimeo. By paying a fee online, viewers were able to watch all the works during a seventy-two-hour period. While the opportunities for presentation and viewing were limited, the artists can be said to have established “a place that is not anywhere” to connect works and audiences through the use of existing services.

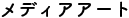

On April 30, FUSE Rintaro opened his Kakurishiki noukou sesshoku shitsu (Isolated close contact room) in the form of a two-person exhibition with poet MIZUSAWA Nao. In this exhibition, FUSE deliberately restricted the Internet’s characteristic of enabling simultaneous access by an unspecified number of people by allowing only one person at a time to enter the room, while on the other hand, he created a kind of personalization using these visitors’ GPS information, thereby giving the exhibition a multilayered site-specificity. This exhibition is still open to the public (as of the time of writing this article in early August 2021), and I would recommend you to experience it for yourself. It is a timely attempt to link FUSE’s interests (the Internet and loneliness) with the situation surrounding the COVID-19 pandemic. His interests also extend to the history of net art, where he speculates on the essence of networks and communication, which he considers cannot substitute for reality (*7).

From Kakurishiki noukou sesshoku shitsu (the Isolated close contact room) online exhibition

From Kakurishiki noukou sesshoku shitsu (the Isolated close contact room) online exhibition

Photo: TAKEHISA Naoki

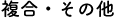

The DOMANI the Art of Tomorrow, an annual exhibition organized by Japan’s Agency for Cultural Affairs as a group exhibition of artists who have taken part in the agency’s overseas study program for emerging artists, was held at the National Art Center, Tokyo in the early months of 2020, and this was followed in July by a special online project put together at short notice entitled the DOMANI plus Online 2020: Living on the Eve. The aim of the organizers was to create an opportunity for young and mid-career artists to present their works during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The website for this exhibition, in which eight artists participated by contributing visual expressions, was designed to allow the viewers to move horizontally from one work to another on a flat screen (creating an abstraction of visitor migration around the real exhibition), and HAYASHI Yoko, the curator of the exhibition, organized the order of the works into a “flow line” based on the characteristics and keywords of each work. In addition to catalog-like contents such as texts by the artists and the curator (*8), the website includes talk events and displays a simple but integrated form. There was also a diversity of visual expression on view in the online exhibition, from artists such as yang02, who brought in synchronicity through participatory live streaming, and AOYAMA Satoru, a guest artist who together with buyers of his works visualized the whereabouts of the works on the exhibition sales website he started during the COVID-19 pandemic.

From the DOMANI The Art of Tomorrow plus Online 2020: Living on the Eve online exhibition

Top: Part of the curator's essay on the exhibition website

Bottom: “Online Talk: KOGANEZAWA Takehito and AOYAMA Satoru” distributed on the same website during the exhibition period

There are also cases where 3D space has been used for online original projects. If I were to categorize them, I would say there are cases where real works are exhibited in a virtual space, and cases where artists attempt to express the works themselves in a way that is unique to virtual space *9. One of the latter cases, the Adventures of Tamabi Sculpture: Return to the Cyber-Sphere, which opened to the public in August 2020, was organized by students of the Department of Sculpture, Tama Art University. The project was produced by the university’s faculty members TAKAMINE Tadasu and KIMURA Takeshi, and TANIGUCHI Akihiko, a faculty member of the Information Design Department, providing supervision and technical guidance. They invited NOSE Yoko, a curator of the Toyota Municipal Museum of Art, as an advisor. TANIGUCHI commented as below.

When you think about what a sculpture is to the limit, it is not absolutely necessary to deal with physical sculptures [...] I think the fact that we were unable to use “physical” sculptures, students were able to consider the question, “What is sculpture in the first place?” (*10).

The 3D virtual spaces and artworks created using the game engine Unity (including those that allow the experiencer to take actions that interfere with the exhibition) reveal the traces of trial and error made by young artists who have temporarily abandoned the constraints of reality. The class materials that accompanied the exhibition also touched on the history of Internet art and online exhibitions, and overall, the exhibition prompted both the creators and the viewers rethink the concepts of “exhibition” and “sculpture.” In general, online exhibitions are enjoyable as attractions that take advantage of new technologies, but what people expect of art are discoveries and experiences that go beyond mere spectacle.

3. Coordination between real and online spaces

From the end of May 2020, when the first state of emergency was lifted nationwide, exhibition activities at “real” venues resumed (although organizers were forced to respond to each subsequent spread of COVID-19 infections and state of emergency declaration). Since entering this phase, I think there has been a growing trend towards preparing both physical and online venues in accordance with their respective characteristics and linking these venues together.

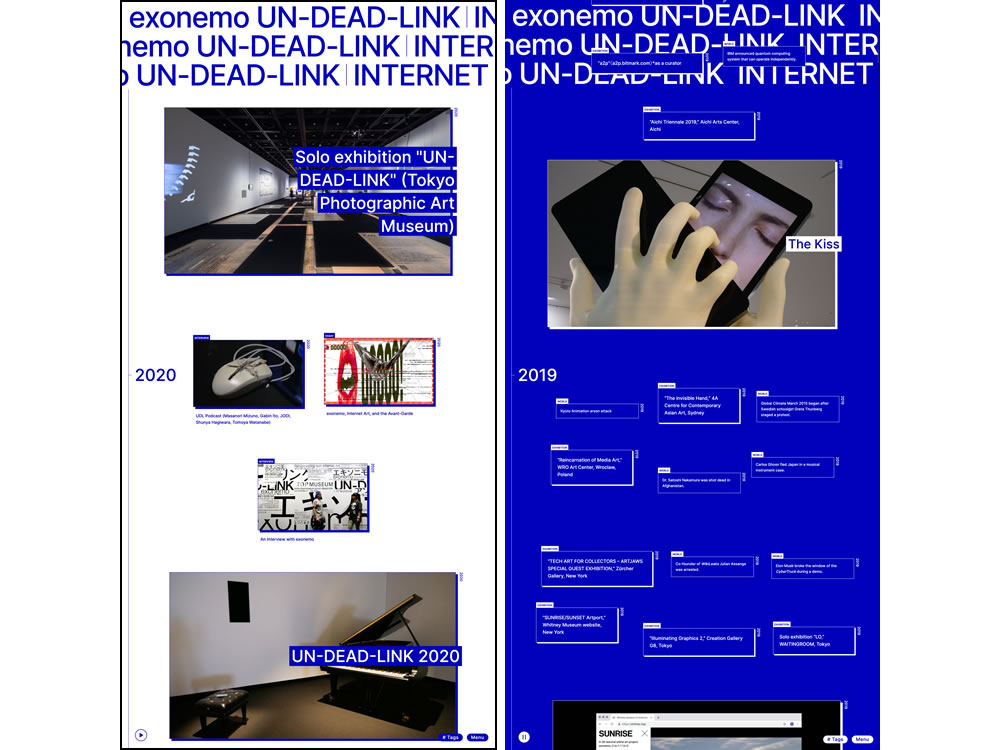

The exonemo UN-DEAD-LINK: Reconnecting with Internet Art exhibition, which opened in August 2020, was officially provided with an Internet venue in addition to a real venue inside the Tokyo Photographic Art Museum. This exhibition focused on the art unit exonemo, who have been active in the fields of Internet art and media art since the 1990s. The real venue served mainly as space for exhibiting their representative works, while the online venue featured the unit’s chronology, an introduction to their works, and a wealth of study articles and interviews. Moreover, in their new works Realm and UN-DEAD-LINK 2020, while dealing with the themes of existence and death, the artists have allowed their work to assume a critical nature by linking the differing experiences at the real and online venues (*11). The exhibition could be described as an attempt to reflect the activities of these artists, who continue to express themselves through the traffic and connection between the real and digital worlds.

DISCODER from the exonemo UN-DEAD-LINK exhibition Courtesy of the Tokyo Photographic Art Museum. Photo: MARUO Ryuichi

DISCODER from the exonemo UN-DEAD-LINK exhibition Courtesy of the Tokyo Photographic Art Museum. Photo: MARUO Ryuichi

From the exonemo UN-DEAD-LINK exhibition internet venue. After the exhibition, the Internet venue remained as an archive (as of August 2021).

From the exonemo UN-DEAD-LINK exhibition internet venue. After the exhibition, the Internet venue remained as an archive (as of August 2021).

Courtesy of the Tokyo Photographic Art Museum.

Photo: MARUO Ryuichi

NTT InterCommunication Center (ICC), a media art gallery in Tokyo, has continued NTT’s exploration of the relationship between the communications technology and the expressive behavior of a given era that began with The Museum Inside the Telephone Network (1991), an experimental event predating the center’s establishment, in which works of art were viewed via telephone, fax, and computer. In other words, from the beginning, the network was considered not as a virtual space but rather as a place where a new reality is constructed, and this attitude was also evident in such exhibitions as [Internet Art Future]—Reality in Post Internet Era (2012). The Museum in the Multi-layered World: Welcome to the Hyper ICC, which opened to the public in January 2021, is a form of collaboration between online and real exhibitions that was born as an extension of this unique practice of the center. The first two online platforms, Virtual Hatsudai and the Hyper ICC, were launched here. Virtual Hatsudai is a virtual space based on the laser-scanned point data of a part of Tokyo Opera City, where the ICC is located. The Hyper ICC, which is located in a corner of Virtual Hatsudai, is a building that changes dynamically and possesses a structure that visualizes the history of the ICC’s activities. Also, while the interior is reminiscent of an actual exhibition room, it makes possible activities and expressions in ways that are free from the physical constraints of the real world.

On top of that, artists produced works that linked the “real display” in the real center and the “online display” in the information space in various ways. For instance, Aguyoshi turned a performance into a work of art using both an avatar and her real body. YAMAUCHI Shota played a sort of game (?) in which the control of a character online became a (sometimes harsh) order to an artist at the real venue. And HARADA Iku presented a series of paintings that originally took virtual space as their starting point and then moved back and forth between real and online, or between 3D and 2D. At this exhibition, it could be argued that the fact that the online venue was architecturally similar to real venue indicates that it was chosen not to replace reality but to extend it (*12).

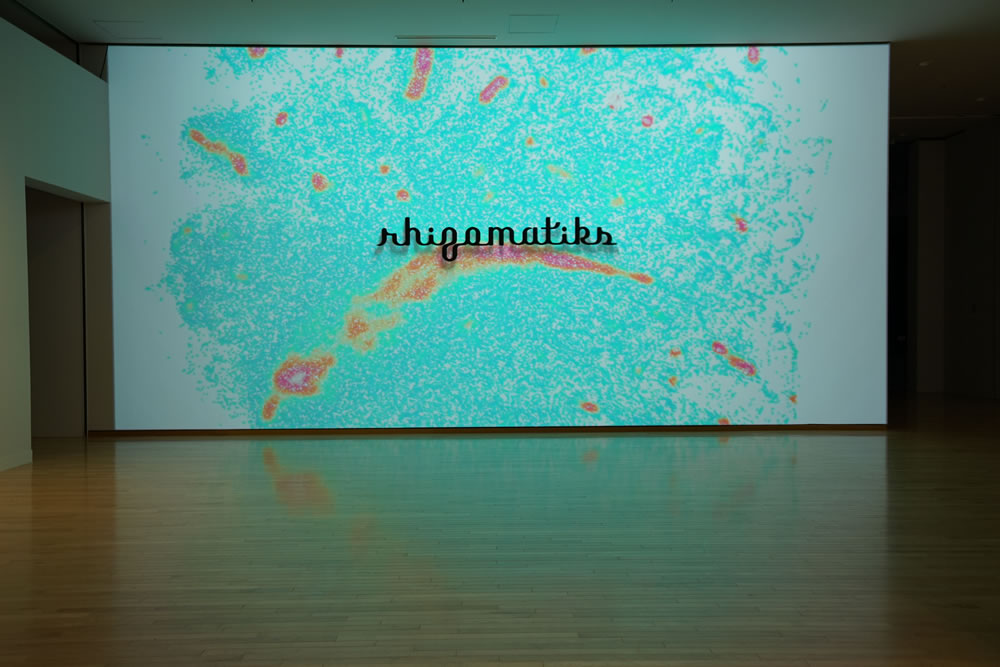

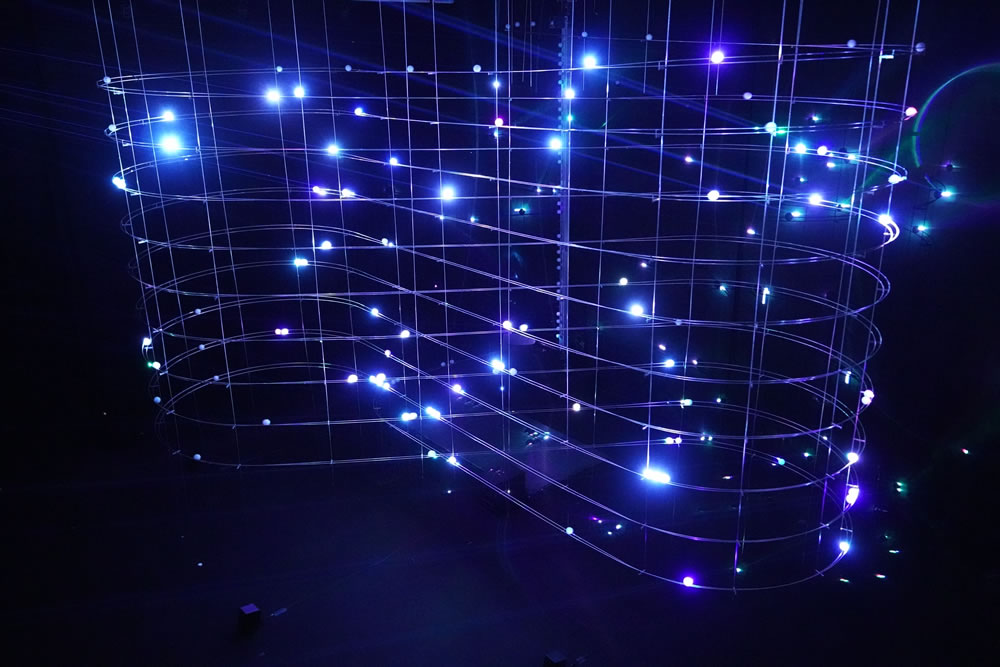

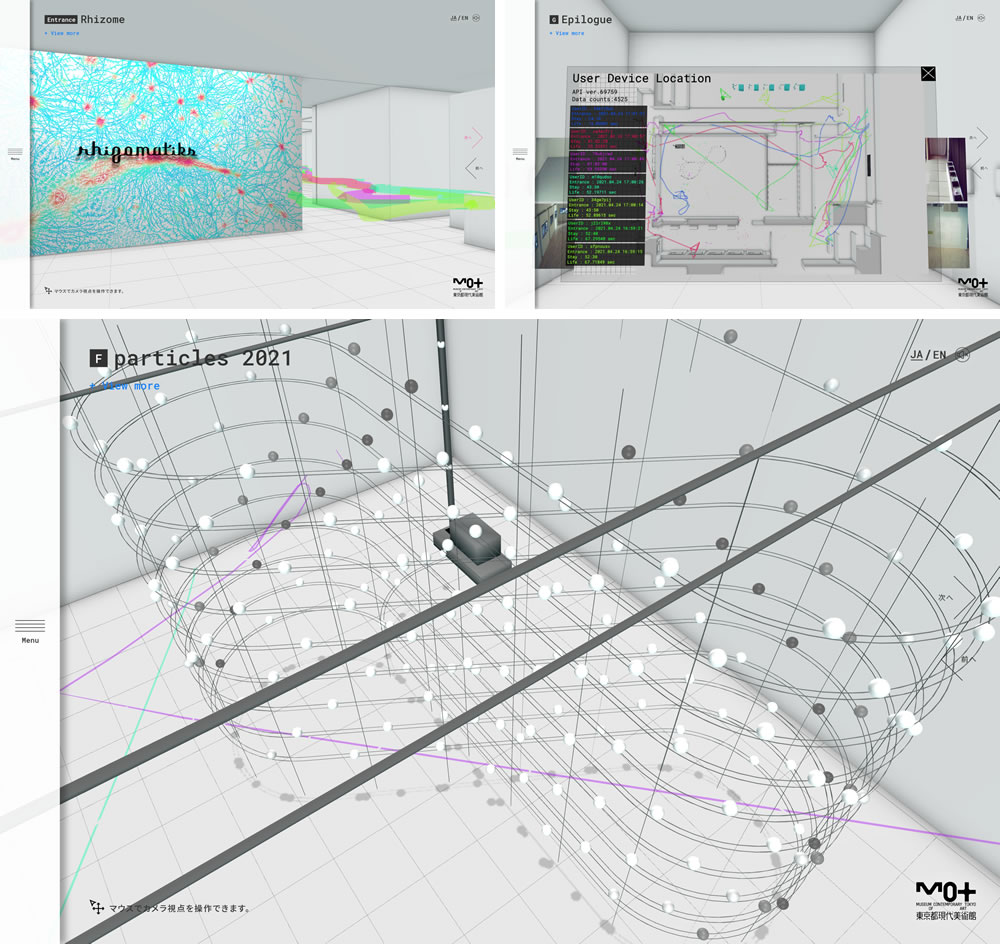

Since then, projects such as the rhizomatiks_multiplex exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo, and New Existentialism exhibition by COBAYASHI Kenta, HIRATA Naoya and yang02 at the Unexistence Gallery on the Internet and on the first floor passageway of HULIC &New UDAGAWA in Shibuya, both of which opened in March 2021, have continued the experiment of combining a real venue and an online venue. In the former instance, the online venue contributed to transforming the project into an art exhibition showcasing the expression of Rhizomatiks, which uses data as a starting point in redrawing the boundaries between the real and virtual worlds. In addition, it appears to be a proposal for how to deliver an exhibition experience with a large volume of information (*13). The latter project is a collaboration between a group of artists with their origins respectively in photography, sculpture, and media art, all of whom are all known for producing representations that update existing reality through digital technology. The surreal yet rich 3D space woven out of the three artists’ works appears in the real building venue like wallpaper in a corridor (in the sense of being extremely flat). It is interesting to see how the traditional value system of virtual = false and real = true has been distorted in their work (*14).

From the rhizomatiks_multiplex exhibition. The entrance to the exhibition site

From the rhizomatiks_multiplex exhibition. The entrance to the exhibition site

Photo by Muryo Homma

From the rhizomatiks_multiplex exhibition. particles 2021 (2021)

From the rhizomatiks_multiplex exhibition. particles 2021 (2021)

Photo by Muryo Homma

From rhizomatiks_multiplex online

From rhizomatiks_multiplex online

In future, the three types of trends I’ve described so far seem likely to continue to deepen and diversify in terms of both technology and expression. (Or will, perhaps, some of them become obsolete?) Moreover, online communication in the art field will no longer be limited to online exhibitions in the narrow sense, but will expand to encompass multiple areas such as learning programs and art projects. From the next article in this series, I would like to discuss these trends while reporting on new cases and people in the field.

(notes)

*1

Marcel PROUST, from La Prisonnière (1923), a volume in the series of novels À la Recherche du Temps Perdu (Remembrance of Things Past). Translated into English by C.K. Moncrieff as The Captive (Random House, 1934).

*2

FUJIKO F. Fujio, Doraemon, Vol. 12, (Shogakukan, 1976).

*3

Apart from online exhibitions via the Internet, there was also The Virtual Museum (1992), a virtual museum-like software packaged on CD-ROM released by Apple Computer Inc. Reference: Riccardo BIANCHINI, “When museums became virtual – 1: the origins,” Inexhibit, 2017

https://www.inexhibit.com/case-studies/virtual-museums-part-1-the-origins/

*4

To the best of the author’s knowledge, there was an exhibition by OKOJIMA Maki at HARUKAITO by island, an art gallery in Tokyo, entitled Bones, the sea inside of body. — Petrified plants (March – April 2019).

*5

For example, the UK-based White Cube gallery is experimenting with an Online Exhibition/Viewing Room Section. Also, the gallery held an exhibition of work by NOMATA Minoru in July 2020.

*6

The following is a related essay.TARASHIMA Satoshi, “ikanai/ikenai hito no tame no digital museums to sore wo sasaeru digital archives (Digital museums for those who can’t or won’t go, and the digital archives that support them” artscape (July 1, 2020). https://artscape.jp/study/digital-achive/10162857_1958.html (in Japanese)

In addition, when museums handle exhibition records that use a specific company’s platform, such as Matterport, as an archive, there will be some debate over how the data should be retained and managed over the long term.

*7

FUSE Rintaro, “Network no naka no anagram shiron” (Anagram Essay in the Network) in LOOP— Film and New Media Studies — a bulletin of the Graduate School of Film and New Media, Tokyo University of the Arts, Vol.11, (Sayusha, 2021).

*8

The author was involved in this exhibition as an editor.

*9

In 1999, the Guggenheim Virtual Museum, an experimental initiative by the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, was set up as a new museum in digital space by the architecture firm Asymptote to house and exhibit cyber art (see the BIANCHINI article referenced above). In Japan too, there are examples of virtual museums such as the IJC Museum, established in 2016. Planned by All Nippon Airways Co., Ltd. (ANA) as a promotion for foreigners visiting Japan, visitors to the website can virtually experience actual works by artists KUSAMA Yayoi, NAWA Kohei, Tabaimo, and others in a circular museum space floating in the clouds. (Tabaimo’s work there reproduces the work she exhibited in the Japan Pavilion at the 54th International Art Exhibition of the Venice Biennale.) The collection of two-dimensional works, sculptures, video installations, etc., allows the IJC Museum serve as a reference point for considering the strengths and weaknesses of this type of approach.

*10

HASHIZUME Yusuke, “Chokoku ya tenrankai no kanousei to fujiyusa wo tou. The Adventures of Tamabi Sculpture: Return to the Cyber-Sphere no kokoromi” (Questioning the possibilities and inconveniences of sculpture and exhibition. An attempt of The Adventures of Tamabi Sculpture: Return to the Cyber-Sphere). Bijutsu Techo Web Edition (August 9, 2020).

https://bijutsutecho.com/magazine/insight/22471 (in Japanese)

This exhibition differs from the other online exhibitions covered in this article in that visitors download an app from the exhibition website in order to experience it. I wanted to introduce it from the perspective of highlighting its initiatives.

*11

“Internet to bijutsukan wo kaijo ni. exonimo hatsu no daikibo kaikoten UN-DEAD-LINK ni miru corona jidai no internet art no kanousei” (The Internet and museums as venues. Viewing exonemo’s first major retrospective UN-DEAD-LINK reveals the potential of Internet Art in the era of COVID-19), Bijutsu Techo Web Edition (August 19, 2020).

https://bijutsutecho.com/magazine/news/report/22529 (in Japanese)

*12

In this regard, I would like to refer to an attempt made at the Illuminating Graphics 2 exhibition (2019, Creation Gallery G8, Tokyo), which was put into practice earlier by TANIGUCHI Akihiko, the exhibition’s co-curator and a participating artist. Here, at the end of the exhibition, TANIGUCHI presented a work that reproduced the entire exhibition in a virtual space (including with some devices that are unique to virtual spaces). Visitors to the exhibition were forced to think about the meaning of the word “original” by continuously experiencing both real and virtual spaces.

*13

At the same exhibition, there were also exhibits of CryptoArt, a digital art-form whose uniqueness is guaranteed by Non-Fungible Tokens (NFT) supported by blockchain technology. There is a lot of discussion about this trend, and of course it has something to do with online exhibitions.

*14

Regarding this exhibition, it seems that there were attempts to sell some of the exhibits online, and the sales formats that were presented varied from physical to 3D model data and software.

*URL links were confirmed on August 3, 2021.