Japanese manga has won enthusiastic fans from all over the world. Do you know that the passions of certain people enabled Japanese manga to be exported, and about the hardships these individuals experienced? In this column, Yukari Shiina, who translates overseas comics and writes articles on the Japanese manga scenes overseas, explores the stories that helped internationalize Japanese manga.

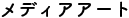

The cover of MANGA

The cover of MANGA

Japanese Manga in the United States

It’s generally believed that the history of the publication of Japanese manga in the United States began in 1987 when Shogakukan Inc. established a subsidiary, Viz Communications, and started its publications. Viz is the first example of a major Japanese manga publisher inaugurating a fully-fledged business in the United States. The company is the first specialized publisher to have brought Japanese manga to the U.S. market.

Despite its fully-fledged business that started in 1987, Japanese manga had been published in various forms previous to that.

Barefoot Gen and I saw it by Keiji Nakazawa depicted these stories based on his own experiences as a Hiroshima atomic bomb survivor. The first one was published in paperback (since 1978) while the latter one was published in comic book (1982). LEED Publishing once independently published the English edition of Golgo 13 without using any local distributors, from 1986. Also, since 1980, anthology magazines like Heavy Metal and Epic Illustrated introduced works by Shinobu Kaze, Go Nagai, and Shotaro Ishimori (at that time), while Frederik L. Schodt’s earliest publication titled MANGA! MANGA! The World of Japanese Comics (1983) covered significant pages for translation of Japanese manga works.

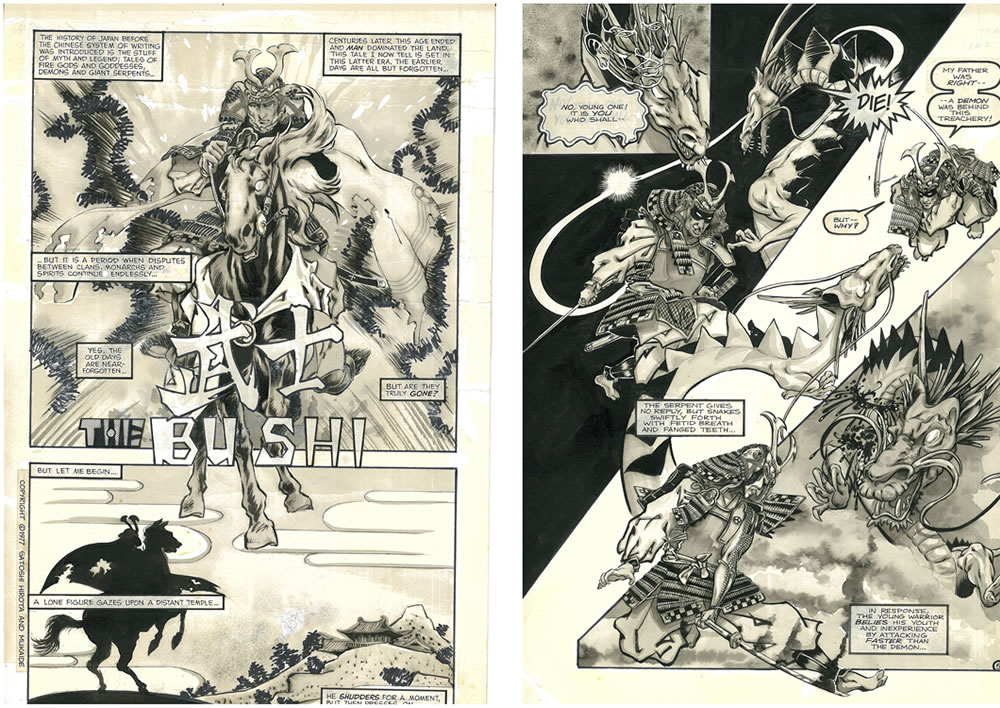

As mentioned, there were several Japanese manga magazines published in the United States before 1987, although the number was small. One of them was a unique publication. Entitled MANGA, it was an 88-page anthology of 10 short stories in both color and black-and-white. Its physical size is a bit larger than ordinary American comic books, rather like the comic magazine size. The publisher, Metro Scope Ltd., mentioned in the magazine, is located in Japan. However, it was hard to find details of the company. The published year was unknown. According to Manga: The Complete Guide (Del Ray, 2007), it was supposedly published from 1980-82, while several websites on comics also presumed 1980-82 or 1984 at the latest (*1).

The stunning roster of authors makes the unique publication more impressive: Hiroshi Hirata, Yosuke Tamori, Yukinobu Hoshino, Katsuhiro Otomo, Keizo Miyanishi, Noboru Miyama, Yoji Fukuyama and Noriyoshi Orai (illustration). In addition, Hajime Sorayama was featured on its cover. The back cover was illustrated by Hiroshi Hirata. Chiki Oya was in charge of coloring the illustration indicated.

A statement on its back cover indicates the publication was the first attempt to introduce Japanese manga to the world’s readers and the joy of helping to deepen understanding of Japanese culture in the West. It is clear that the core purpose of the publication was based on the introduction of Japanese manga to the English-speaking world. The copyright page features names of artists and writers who were active in the American comic industry, alongside Japanese people’s names.

How did the MANGA anthology magazine come to be published in the early 1980s when not many people knew the meaning of the word “manga”?

For me—a researcher who has been studying history of Japanese manga in the United States—the publication has long been a mystery. Recently, I had the opportunity to hear the story-behind-the-story, directly from Masaichi Mukaide, the publication’s editor.

Based on a talk by Mr. Mukaide, this article tries to clarify how the publication was produced and finally came out, along with the comic/manga scenes in the two countries at that time. I’d like to start this article with the moment when Mukaide encountered one comic magazine published in the United States. (Hereafter, the titles for everyone are omitted)

Star*Reach

Masaichi Mukaide, who worked as the editor-in-chief of the MANGA anthology magazine, was born in 1952 in Tokyo. A student movement was on the rise in Tokyo in the early 1970s while he was a university student. He spent lots of time on his hobby as classes were canceled quite often. He was familiar with Japanese manga magazines like the COM and GARO monthly manga anthology magazines. Later, he showed an interest in American comics. He spent his time with his friends, including ones at other universities, as they their shared the same hobby.

When I was a university student, I frequently went to secondhand bookstores like BookBrother and Tokyo Taibunsha in Tokyo’s Jinbocho to find the American comics I liked. At that time, not many Japanese read American comics, so that I may have attracted some attention. Several people talked to me while I read the comics, and then we would hang out.

At that time, translated American comics were very scarce, so most comic lovers read the original English editions. Many of his friends were fluent in English. One was Hisashi Kuroma (1951-1993). Kuroma later became a translator of science-fiction novels and also introduced American comics under his pen name, LEO. Through him, Mukaide once worked part time for Kiso Tengai, a newly published science-fiction magazine.

I once submitted a collaborative piece with Kuroma for SF Magazine, published by Hayakawa Shobo when the magazine collected manga works. It failed, but we drew a heroic fantasy like the Conan series. At that time, science fiction was defined as Asimov, so that heroic fantasy didn’t have much appeal, so to speak. The original art works were not returned to the authors (us). It seemed that the publisher took the liberty of discarding it. I was informed of this later by Kuroma.

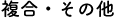

In the meantime, Mukaide encountered Star*Reach, an anthology comic magazine published in America. Inaugurated in 1974, Star*Reach had been published in 18 issues until 1979. It was a science fiction and fantasy magazine that carried works in black-and-white. As I write later in this article, this magazine was talked about by comic historians in following years, for certain reasons even though its publication period was not very long.

Star*Reach was inaugurated by Mike Friedrich, who worked about six years as a writer for major comic publishers including Marvel Comics and DC Comics. He established Star*Reach Productions and inaugurated the magazine in 1974 as he served as its editor-in-chief. When Star*Reach was launched, underground comics that came out from the latter half of the 1950s were in sharp decline for several reasons, while new comics were born on the American comic scene. The underground comic movement that went against the industry’s self-regulation code established in 1954 was on the rise more, corresponding with a counterculture. The trend prompted creators to reconsider comics as a medium of self-expression. Once the underground comics faded away in the 1970s, then a new movement appeared to find a new expression of comics not related to the counterculture. At that time, works of science fiction and fantasy were particularly prominent following the popularity of the science-fiction genre since the late 1960s.

Star*Reach was an early anthology magazine comprising science fiction and fantasy. Under Friedrich’s network, such well-known artists/writers as Howard V. Chaykin and Barry Smith joined the magazine and created their own works freely without being bound by the code. Star*Reach permitted the authors to hold the rights, which major publishers had not allowed them at that time.

Including works inserted in Star*Reach, new types of comics that appeared at this time were called “New Wave” or “Newave,” or also “ground level” (between underground and over ground). Today, those works created around that time are considered that they have built a bridge between the alternative comics and the underground comics (*2).

Mukaide liked Star*Reach as soon as he saw it.

I have archived all the copies of Star*Reach from its inaugural edition. I got it because it looked interesting when I saw it in an overseas comic catalog that one of my friends had. It very much suited our feelings once I read it. So, I submitted an original art work entitled “The Bushi” that I created with that friend. I promptly sent the original art work. because “copy” meant blueprints at that time. Mike had highly evaluated it, and we started corresponding. I think I got on well with Mike.

“The Bushi” appeared in the 7th issue of Star*Reach (1977) (*3). Some sources say it is the first Japanese manga published in the United States (*4). The work itself was evaluated as “somewhat American.” Although it is a historical Japanese setting, “There is very little to indicate that the creators themselves were also Japanese. Mukaide’s artwork is not all that different from many of the other comics found in Star*Reach” (*5). Mukaide received feedback (in letters) of “The Bushi” from American artists, so the piece appealed to some readers.

To be honest, I wanted to be an artist of American comics, or a manga artist. However, (later,) when I met with Hiroshi Hirata, I gave up my dream as I was much impressed by his works. His works were gorgeous.

The cover of the Star*Reach, 7th issue

The cover of the Star*Reach, 7th issue

“The Bushi”

“The Bushi”

Until 1979, seven works in total of Mukaide (including the piece he worked on with an American writer) were published in Star*Reach and Imagine (1978-79). Imagine was inaugurated by Friedrich as a sister magazine of Star*Reach.

Such activities by Mukaide were featured in the Japanese edition of STARLOG’s January 1980 issue, marking a Japanese artist’s debut in an American comic magazine. The magazine was inaugurated in 1978. Kuroma contributed to it not just by writing about American comics but aggressively introducing overseas cartoon works focusing on science-fiction and fantasy genres (*6). One person who saw the feature article contacted Mukaide. The person talked to him about his idea to publish Japanese manga in the United States and asked Mukaide to help him.

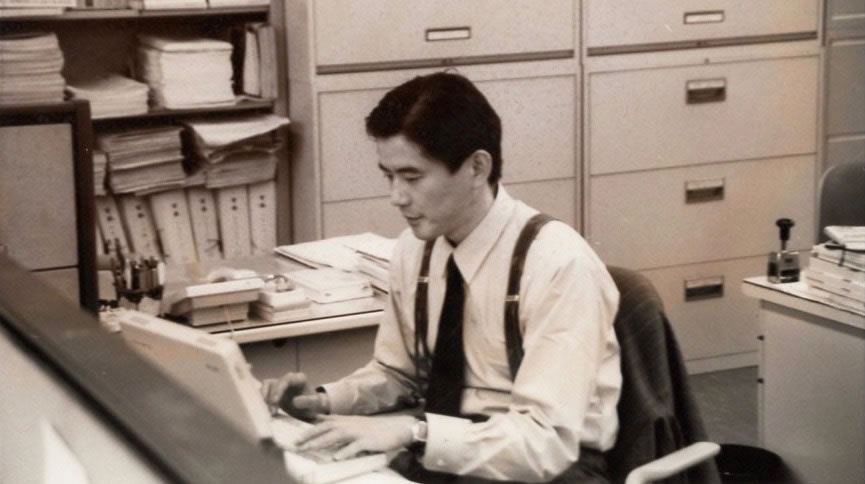

Masaichi Mukaide when he worked for MANGA magazine

Masaichi Mukaide when he worked for MANGA magazine

Production of MANGA

Here, I tentatively set a certain person as X. X has a proven track record in an industry other than publishing. For some reason, X had an interest in the business of Japanese manga publishing in the United States. Mukaide had provided consultation for X to produce anthology magazines like Star*Reach to introduce one-shot comics by Japanese manga artists.

As I produce a magazine, I asked help from friends in the field of American comics. Once I explained to Mike, saying, “I’d like to produce such magazines like...” then, he introduced me to several persons. However, we selected manga artists in Japan for publication.

Mukaide wanted to introduce Japanese manga that would be accepted in the United States. At the same time, he wanted to publish works by his favorite manga artists, no matter what. So, he contacted those manga artists directly on his own. Although at first he didn’t have their contact information, he was able to find them in a telephone directory for media people quite easily. At that time, personal information was not as secure as it is today.

I was truly happy, as all the contacted manga artists accepted our request. They were all cutting- edge artists in Japan at the time. All were highly popular manga artists so that I thought most of those may have turned us down. I believe they responded to our strong passion of wanting to introduce Japanese manga to the world. Finally, all created new works, except Katuhiro Otomo and Noriyoshi Orai.

All the published works were science fiction or fantasy, apart from one historic drama created by Hiroshi Hirata. Mukaide’s own work was also published.

One source says that MANGA made an impression as a Japanese edition of Heavy Metal, a science- fiction fantasy magazine that was highly popular in the United States at that time (*7). One blog indicated that the magazine was more like “North American comics in the early 1980s” rather than “Japanese manga” (*8). That was actually intended, and at the same time was the result of the reflection from the trend of the times, not just a preference for manga by Mukaide and other Japanese staff members.

On the one hand, Mukaide and his friends who were familiar with American comics had known the difference between Japanese and American comics/ manga. So, they thought Japanese manga wouldn’t have been accepted by American readers if they brought it as they have done in Japan.

During the editing process, people who were introduced to Mukaide by Friedrich were highly involved. They included Lee Marrs, who debuted with an underground comic, Steven Grant, who later worked for Marvel and DC, and Larry Hama, who worked as an actor, musician, writer and artist.

As adapters, their duties were correcting parts unacceptable to American readers because they were too Japanese. For instance, take Keizo Miyanishi’s “MidSummer Night’s Dream,” which depicted the night Hikaru Genji met a mysterious woman. The original didn’t have much dialogue and narration, so Marrs added lots of it.

This work was published in the inaugural issue of Quarterly Comic Again (Summer Issue, August 1984) (*9) in English with commentary in Japanese. Several other works that once appeared in MANGA were published in Japanese magazines.

Depending on the situation, we first created a layout of artworks and scripts with English translation. Then, we heard suggestions from the American side and did rearrangements. American people didn’t get some of our meaning from direct translations. For manga artists, we explained to them that readers overseas may have a different way of feeling. We asked them to understand our rearrangements. For lettering, there were no specialists in Japan, so we phototypeset and pasted on word balloons.” The toughest job was communications during our work with people in the U.S. It was the same when my works were published in Star*Reach and Imagine. It had taken a lot of time. Today, we have e-mail communications, but nothing like that at that time. It took more than one month for one communication once in a while. Even so, I believed it was important to have their help as they knew comics and commercial products would have been perfect and accepted in America.

At last, it had taken nearly two years since X introduced the idea. The anthology magazine was completed and hit in the shelves in book stores in 1982. As Mukaide desired, not only were the manga artists published in the magazine, but the quality of the paper and printing were gorgeous. Mukaide was perfectly satisfied with the magazine.

At that time, I realized that no other Japanese had done what I had done. I felt even more passion to create such a great book. I didn’t care if it was the first one or the second, I just wanted to create one definitive piece.

However, Mukaide encountered something unexpected. It was MANGA’s distribution system in the United States.

Mike had picked a suitable distributor for MANGA. However, in line with X’s intention, we had to use a Japan-related distributor. So, the magazine was not distributed through America’s “direct market.” MANGA was only sold in Japan-related book stores in the United States at that time.

“Direct market” in this context indicates the market specialized in comics. Today, comics can be sold in book stores in the United States. However, they were sold at newsstands or stores specialized in comics for long time. Although the pros and cons of the direct market which was established in 1970s have been debated in recent years, in the 1980s, when MANGA was inaugurated, a number of comic shops in the United States were greatly increasing in number in response to a surge in the value of comic books as investment targets. Friedrich successfully published Star*Reach as an anthology magazine specializing in the market. Then, he was evaluated for his skills and was appointed as a sales director in charge of the direct market at Marvel (*10). When Viz published Japanese manga for the first time in the United States, it had expanded its sales through the direct market. Also, when the Japanese manga boom arose in the United States in the 21st century, it was an element of success that it was sold in a different place from the previous sales channel. The importance of reaching the target consumer is the same for any product, not just its quality.

In the end, MANGA did not sell well. The stock piled up.

It may not be appropriate just to blame the distribution network for the failure to sell well. However, it is sad to think that that was the reason it might have not reached the target readers.

We had a plan to publish the second issue of MANGA and to sell it overseas first. Then for the Japan market, we were planning to place a parallel translation (bilingual) at the back of the book so that readers could study English as well. However, it was all for nothing, because the magazine did not sell well. Stocks piled up. So, we sold them in the foreign-book corners in Japanese book stores. MANGA magazine was sold along with American comics, bande dessinee (BD) such as Mobius collections.

Although the magazine did not sell well in the United States, it cannot be said that it was a complete failure in terms of introducing Japanese manga to America. The two major U.S. comic publishers, DC and Marvel as well as independent Eclipse Comics, which saw MANGA’s cover story “Two Warriors,” requested Hiroshi Hirata to create a work for them.

As Hirata accepted the request, Mukaide and Friedrich worked as liaisons between Hirata and overseas. Hirata agreed to publish his work with DC Comics. However, he was not able to meet his deadline because he had a hard time creating the work based on the script prepared by the publisher along with the corresponding work with overseas, which he was not familiar with. Finally, Hirata’s work, entitled “Samurai: Son of Death,” was published by Eclipse Comics. This was in 1987, five years after MANGA was inaugurated.

Personally, I was ready to start a publishing agent for overseas, after Hirata published “Samurai: Son of Death.” Mike had also helped me find letterers and writers.

Mukaide became busy, as he worked for a company. He was not able to serve as an agent exclusively so he was trying to find publishers whom he could cooperate with. The publishers listened to him but didn’t make any moves to publish manga overseas. Nothing had come to fruition. Mukaide’s experiment may have been too far ahead of its time, in many aspects.

Japanese and American fandom

It seems that manga artists published in the MANGA anthology magazine overlap with manga artists who produced works called “New Wave Comics” in Japan at that time. It is hard to explain what a New Wave Comic is, but works that transcended existing genres appeared in the latter half of 1970s and ’80s and were given the moniker by manga critics.

Fortuitously, from the mid-1970s to the first half of 1980s in America, works in search of new expressions so called the “New Wave” or “ground level” drawing attention. The term ground level was said to have been coined by Friedrich. Star*Reach was a magazine that represented “New Wave” rising from “ground level,” not from “underground” (*11).

The background was the science fiction boom. With the success of the Apollo 11 moon landing in 1969, public interest in science increased. In the late 1970s, the “Star Wars” movie was a hit. The genre of science fiction began to gain new fans both in Japan and the United States. In the U.S., STARLOG magazine, which captured science fiction in a visual form, was inaugurated in 1976. Heavy Metal magazine, the American edition of French Metal Hurlant magazine, was inaugurated in 1977. The number of independent comic publishers producing science fiction and fantasy works was increasing.

In Japan, STARLOG, Kiso Tengai SF Manga Dai Zenshu, Monthly Superman were inaugurated in1978. Popeye and other general magazines featured science fiction quite frequently. Various media attracted the attention of the younger generation at that time with the topic of science fiction beyond national borders, until the early 1980s.

In Japan and the United States, comics and manga fandoms were developed by science-fiction fandoms as incubators. It is not simply comparable to think about the complex cultural context of each country. However, it is interesting that all the Japanese and American comics and manga were facing the New Wave in different locations, centered on the science-fiction genre.

In Japan, when we talk about the history of postwar manga, in general, as if everything began with Osamu Tezuka. Other than Tezuka, exchanges and interactions with foreign countries are abandoned in many contexts quite often. Concerning that point, it can be said that MANGA was an interesting attempt to show some aspect of Japan-U.S. cultural exchange at that time.

It is of no help to bring “if” into history. But I thought “if” the MANGA anthology magazine had reached the correctly targeted readership in the United States in the early 1980s, then….

(notes)

*1

Ash Brown, “Random Musings: Spotlight on Masaichi Mukaide,” Experiments in Manga, posted in August 2014.

http://experimentsinmanga.mangabookshelf.com/2014/08/random-musings-spotlight-on-masaichi-mukaide/

Brian Hibbs, “My Life is Checked with Comics #19a Manga,” The Savage Critics, September 21, 2009.

https://www.comixexperience.com/savagecritics/reviews/my-life-is-choked-with-comics-19a-manga

*2

The following were referred regarding American comic scenes such as

“new wave” and “ground level”:

Randy Duncan, Matthew J. Smith, The Power of Comics: History, Form and Culture, Continuum, 2009, pp. 63-7.

Jean-Paul Gabilliet (translated by Bart Beaty and Nick Nguyen), Of Comics and Men: A Cultural History of American Comic Books, University Press of Mississippi, 2010 (originally published in 2005 in French) pp. 49-86.

*3

“武士:THE BUSHI,” Script/Satoshi Hirota, Additional Dialogue/Mike Friedrich, Artwork/Mukaide, Star*Reach, #7, January 7 1977, Star*Reach Productions.

*4

Dan Mazur, Alexander Danner, Comics: A Global History, 1968 to the Present, Thames & Hudson, 2014.

Also, there are several different stories on Japanese manga first published in the United States, e.g. “Sakura Gaho (cherry blossoms magazine)” by Genpei Akasegawa, “Akame (red eyes)” by Sanpei Shirato, “Nejishiki (Screw Style)” by Yoshiharu Tsuge, all appeared in an academic theatrical journal named Concerned Theatre Japan Vol. 2, Issue #1 in 1971 were among others which was said to be the “first” manga script introduced in the United States.

*5

Ash Brown, “Random Musings: Spotlight on Masaichi Mukaide,” Experiments in Manga, posted in August 2014.

http://experimentsinmanga.mangabookshelf.com/2014/08/random-musings-spotlight-on-masaichi-mukaide/

*6

STARLOG January 1980 issue, p. 26.

*7

Jason Thompson, Manga: The Complete Guide, Del Rey, 2007.

*8

Brian Hibbs, “My Life is Choked with Comics #19b Manga,” The Savage Critics, September 21, 2009.

https://www.comixexperience.com/savagecritics/reviews/my-life-is-choked-with-comics-19b-manga

*9

Kikan Comic Again (Quarterly Comic Again) Summer Issue, August 1984, Nihonshuppansha Inc. pp. 155-162.

*10

Kim Thompson, “Reaching for the Stars with Mike Friedrich,” Comics Journal, #71, 1982, pp. 79-92.

*11

Roger Sabin, Adult Comics: An Introduction, Routledge, 1993, p. 270.

*URL links were confirmed on April 20, 2020.

Masaichi Mukaide

Born in 1952 in Shinagawa-ku, Tokyo. After graduating from the Department of Law, the Faculty of Law at Chuo University in 1976, he joined Chuokeizai-sha Inc. In the early 1980s, he served as Editor-in-Chief for the MANGA anthology magazine, which carried Japanese manga scripts and was published in the United States. He resigned from the company in 2017.