From May 23 to August 26, 2019, a manga exhibition titled “Citi exhibition Manga” was held at the British Museum in London, known as one of the biggest museums in the world. The exhibition received a lot of attention from all over the globe because it was put on by the well-known organization, the British Museum, and was definitely the biggest manga exhibition held outside of Japan. In fact, about 180,000 people visited the exhibition during the three-month period, setting a new record for the museum, as its feature exhibition. This report highlights the contents and impact of the exhibition.

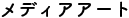

The exterior of the Sainsbury Exhibitions Gallery

The exterior of the Sainsbury Exhibitions Gallery

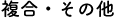

To the world of “Manga” with a rabbit as a guide

In the Sainsbury Exhibitions Gallery at the British Museum, this exhibition starts with Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865) by Lewis Carroll. Like Alice following the rabbit, exhibition visitors arrive from the United Kingdom to a mysterious world of “manga” while following rabbit illustrations. This beginning is related to the appearance of Mimi-chan in many spots throughout the exhibition; Mimi-chan is a rabbit character created by Fumiyo Kono, in the style of Choju jimbutsu giga (Scrolls of Frolicking Animals and Humans) created about the 12th or 13th century in Japan.

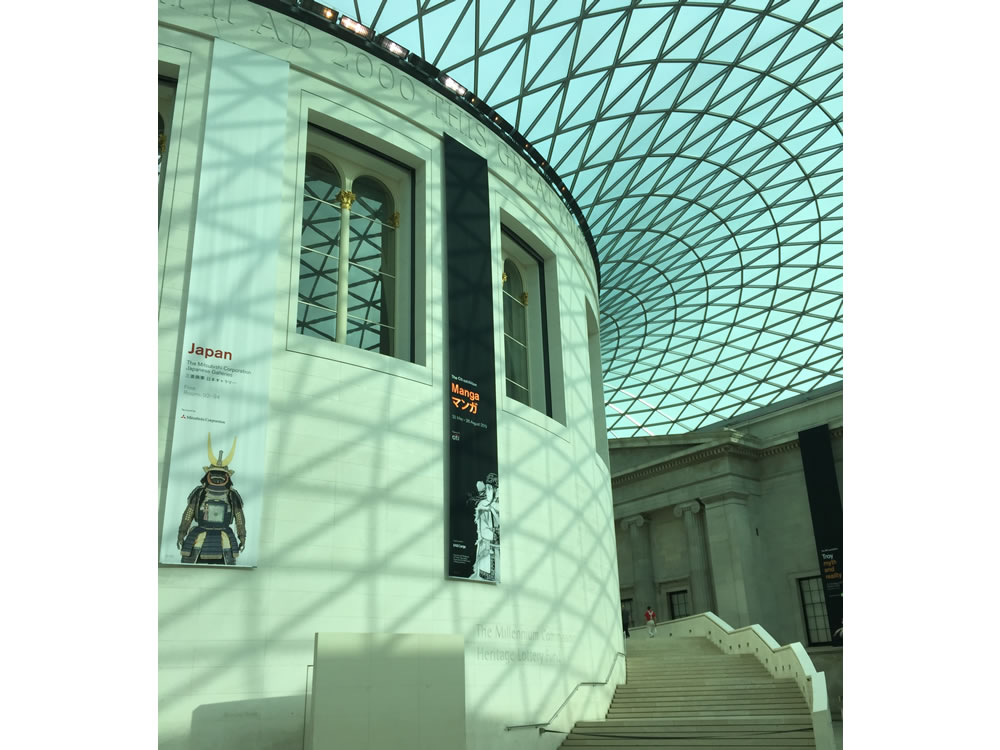

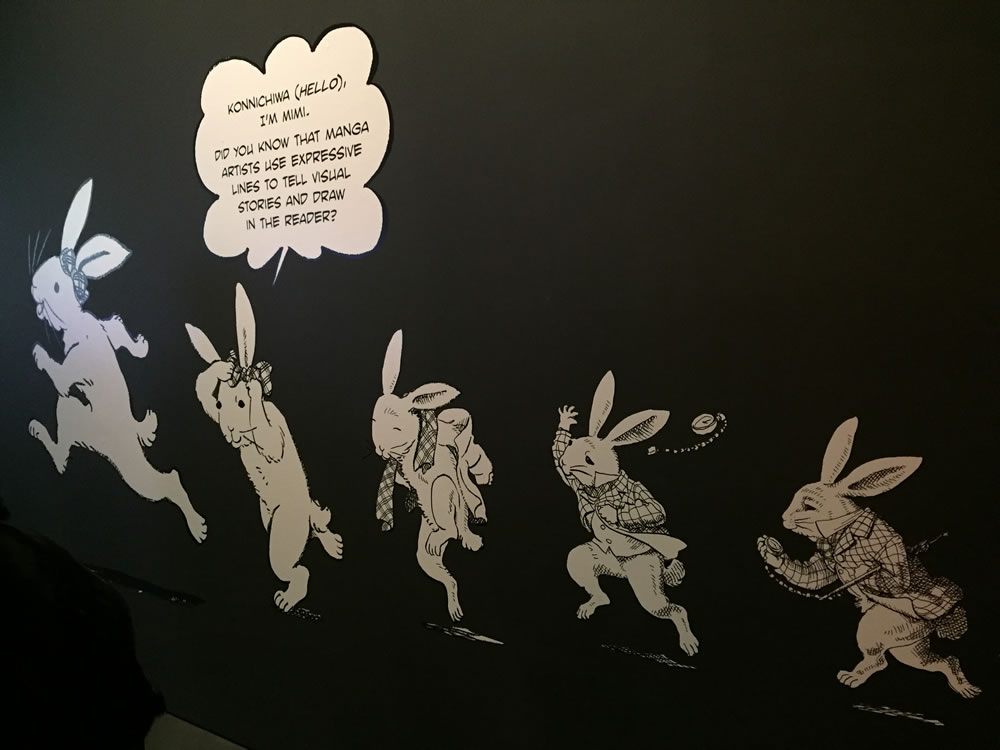

The entrance of the exhibition venue (left), A panel of Alice at the beginning of the exhibition site (right)

The entrance of the exhibition venue (left), A panel of Alice at the beginning of the exhibition site (right)

“Mimi-chan” is a character from Giga Town Manpu zufu (Asahi Shimbun Publications, 2018) by Fumiyo Kono.

“Mimi-chan” is a character from Giga Town Manpu zufu (Asahi Shimbun Publications, 2018) by Fumiyo Kono.

Explaining the basics of manga

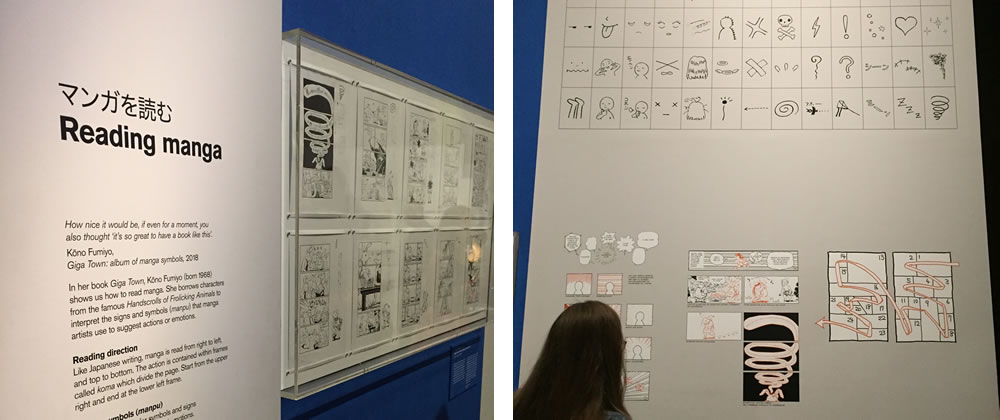

This exhibition consisted of six zones, and through each zone, manga culture was viewed from different perspectives. In the first zone titled “The art of manga,” how to read manga and the process of production from drawing until publication were featured. It was unique in that it included explanations about the reading order for panels and information about manpu (manga symbols), which are often considered common sense in Japan and are not usually presented in manga exhibitions. Also, there were some panels through which visitors could learn about the structure of manga not only by texts but also by illustrations and original drawings of Giga Town Manpu zufu (Asahi Shimbun Publications, 2018) by Fumiyo Kono. In addition, manga drawing tools and videos that had been taken at manga editors’ office were exhibited in this zone to show the background of manga production.

In the section of “Reading manga,” original drawings of Giga Town Manpu zufu were exhibited (left) and also the way of reading manga was explained by using the same manga (right).

In the section of “Reading manga,” original drawings of Giga Town Manpu zufu were exhibited (left) and also the way of reading manga was explained by using the same manga (right).

Tracing the history of manga

In the second zone, called “Drawing on the past,” Ukiyo-e a genre of Japanese art flourished in the Edo Period (1603-1868) and illustrations drawn from the Meiji Era (1868-1912) to the early Showa Era (1926-89) were showcased. Those works are often regarded as ancestors of manga. In the section of “Tezuka arrives” in this zone, Osamu Tezuka’s representative works, such as Treasure Island (1947), Astro boy (Published 1952-68 in Shonen) and more, were displayed. Comics by the Walt Disney Company and a part of Metropolis (1927), a movie directed by Fritz Lang were exhibited to indicate connections with Tezuka’s works. Through original drawing of several manga titles including Dragon Ball (1984-95) by Akira Toriyama and Sailor Moon (1992-97) by Naoko Takeuchi, the “Manga styles” section illustrated the reasons that manga is drawn in black and white and the features of each manga genre’s visual expressions.

Furthermore, in the second zone, a big picture of “Comic Takaoka,” a book store in Jimbocho in Tokyo that has closed down in March 2019, was shown and it made visitors think about the fact that the media of manga also change their shape with the times.

A corner mainly for Tezuka’s works

A corner mainly for Tezuka’s works

A big photo panel to show the interior of “Comic Takaoka”

A big photo panel to show the interior of “Comic Takaoka”

Diversity of themes that manga shows

The “diversity” of themes is often said to be one of the best features of manga and this was introduced through zone 3, “A manga for everyone.” It presents the attraction of well-known themes for manga, such as “Sports,” “Past worlds” and “Horror,” with original drawings of manga titles dealing with each theme. The exhibited works in this zone are: Cyborg 009 (published intermittently between 1964-92) by Shotaro Ishiomori, Ashita no Joe (1968-73) written by Asao Takamori, drawn by Tetsuya Chiba, Toward the Terra (1977-80) by Keiko Takemiya, Captain Tsubasa (1981-88) by Yoichi Takahashi, ONE PIECE (1997-present) by Eichiro Oda, My Brother's Husband (2014-17) by Gengoroh Tagame, and more. There is no doubt that it was a precious opportunity for all of the visitors to see original drawings and replicas of manga titles with different themes and genres from a range of time periods, all visible in one place.

In the zone 3, representative of Japanese manga titles from different genres were introduced.

In the zone 3, representative of Japanese manga titles from different genres were introduced.

Manga, merging into Japanese society

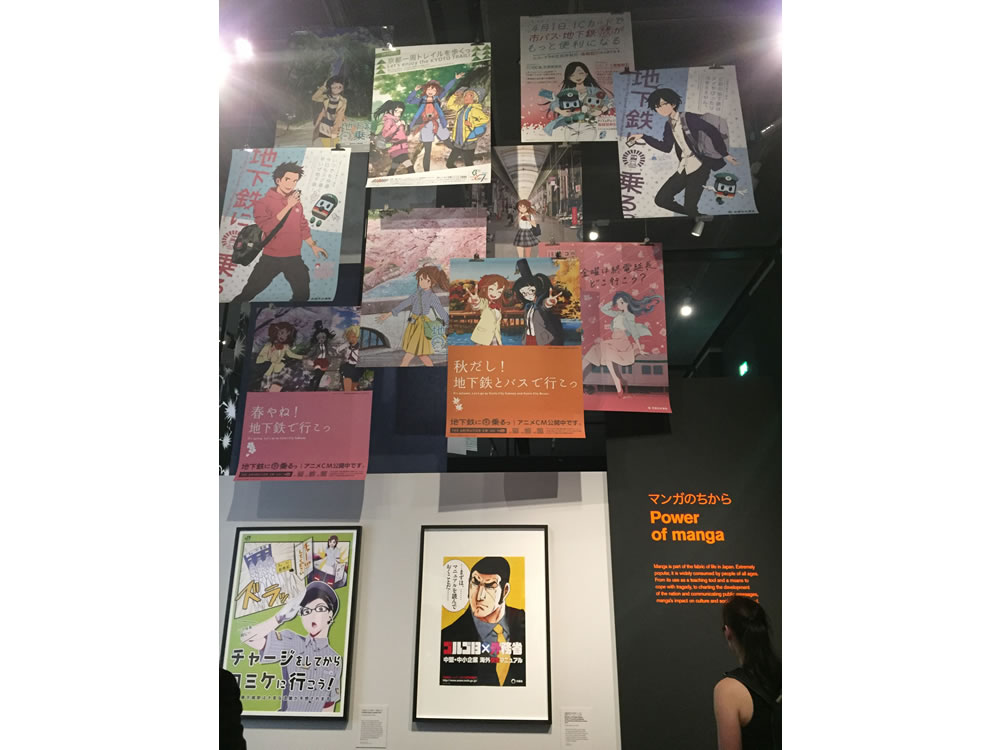

“Power of manga,” the fourth zone, was composed of content that focused on the relation between manga and the society. It showed manga culture that is deeply connected with everyday life in Japan by displaying promotional posters and advertisements with manga-styled characters on them. There were also cosplay outfits that could be tried on in a corner of this zone and some visitors were enjoying cosplay there.

In the zone 4, posters with manga-styled characters on them were on display.

In the zone 4, posters with manga-styled characters on them were on display.

In the section of “Manga and museums,” connections between the British Museum and manga was mentioned. The British Museum has been collecting manga drawings for over 10 years and this exhibition is not its first manga exhibition. “Professor Munakata's British Museum Adventure” (by Yukinobu Hoshino, published in Munakata kyoju ikoroku 2010-11) is a part of their collection. As a case in point from Japan, this section introduced Kyoto International Manga Museum and exhibited elaborate reproductions of manga called Genga’ (Dash), which are produced by the manga museum and Kyoto Seika University International Manga Research Center. Moreover, this zone spotlighted manga as an influential medium by displaying manga titles that generated a social reaction, such as Ano hi kara no manga (2011) by Kotobuki Shiriagari, Ichi-F: A Worker's Graphic Memoir of the Fukushima Nuclear Power Plant (2013-15) by Kazuto Tatsuta.

A group of unique characters and Shintomi-za yokai hikimaku

In the zone 5 under the title named “Power of line,” manga of several artists with different drawing styles were showcased with the main character of each title. Some manga fans were talking with enthusiasm in front of their favorite character or taking pictures of it. The most noticeable work in this zone was Shintomiza yokai hikimaku (Theater curtain of the Shintomi-za with yokai drawings) (1880) by Kyosai Kawanabe (1831- 1889), a Japanese artist. Exaggerated expressions in this huge painting, which was created by Kyosai in 4 hours, suggest there is a connection with manga.

Shintomi-za yokai hikimaku (Theater curtain of the Shintomi-za with yokai drawings) by Kyosai Kawanabe. Ichikawa Danjuro IX and Onoe Kikugoro V, famous kabuki actors at that time, were models of the yokai in the painting.

Shintomi-za yokai hikimaku (Theater curtain of the Shintomi-za with yokai drawings) by Kyosai Kawanabe. Ichikawa Danjuro IX and Onoe Kikugoro V, famous kabuki actors at that time, were models of the yokai in the painting.

Every time a manga exhibition that exhibits various titles like the Citi exhibition Manga opens, many manga fans tend to ask: “Why are those other famous titles not here?” However, it is impossible to exhibit all of the masterpieces in the manga history, thinking about the size of the Japanese manga market and the number of titles that have been published in the past. In addition, there are manga titles that cannot be showcased because of manga artists and publishers’ circumstances. With this background, it can be said that the manga titles selected by the British Museum are reasonable and well-founded enough to introduce the whole of manga culture.

Manga crosses media and borders

The last zone “Manga: no limits” focused on manga culture expanding across media and borders. Mediamix was one of the key terms in this zone and a fusion of manga and other media was shown in various forms; there were anime and games produced based on manga and manga or anime titles that are based on video games, such as Pokémon (Pocket Monster) series (1996-present) as well as contemporary artworks inspired by manga were on display. A section of Studio Ghibli that shows the background of the creation of it was also a part of this zone. At the end of the exhibition, three original drawings especially drawn for this exhibition by Takehiko Inoue, the author of Slam Dunk (1990-96) and Vagabond (1998-present), were exhibited to conclude.

In the section called “Convergence,” Pokémon and other works were showcased (left). My Family Tradition (detail) by Rieko Akatsuka, created under the inspiration from onomatopoeia in manga (right) © Akatsuka Rieko

In the section called “Convergence,” Pokémon and other works were showcased (left). My Family Tradition (detail) by Rieko Akatsuka, created under the inspiration from onomatopoeia in manga (right) © Akatsuka Rieko

Visual expressions of manga, such as “concentrating lines,” were used on some spots at the exhibition venue.

Visual expressions of manga, such as “concentrating lines,” were used on some spots at the exhibition venue.

“Manga exhibition”: pros and cons

The exhibition was very impressive and worth seeing not only because of its size but also because of its focus on Japanese manga culture from different vantage points. It was informative for both manga fans and people with less connection to manga, but what comes next after this exhibition for the general public? People are already looking forward to seeing what kind of manga exhibition the British Museum will present next.

In the United Kingdom, the host country, there were many favorable opinions. However, au contraire, there were also not a small number of criticisms, including a review of The Guardian: “(…) We go there to have our eyes opened to artistic and historical wonders, not to get more of what’s on offer everywhere, 24/7. This exhibition is a tragicomic abandonment of a great museum’s purpose.” It is not surprising to have pros and cons, thinking about the fact that even some manga fans or artists argue that “manga is to read, not to see in an exhibition.” What this tells us might be that the ways to enjoy manga are developing more rapidly then the speed of our perception on manga changes. After all, there also used to be these kinds of critical opinions addressed to manga exhibitions held in Japan. Nonetheless, there are several manga-related museums now and a culture of manga exhibition has recently been taking root. In view of the case in Japan, it can be thought that manga exhibitions may find a place even in countries outside of Japan in the near future.

Despite the arguments for and against the manga exhibition at the British Museum, as mentioned at the beginning of this report, it set a record with around 180,000 visitors, which was an unprecedented event as a charged temporary exhibition. Moreover, it was found that approximately 20% of the visitors were under 16 years old. These numbers are absolutely significant for the British Museum, which is known to have relatively more visitors from an older age group. Even before the Citi exhibition Manga, due to disinterest of younger generations in museums, some museums have held manga exhibitions as a possible solution to their concerns. The success of the manga exhibition at the British Museum may have encouraged more museums in the world to think about incorporating manga, and it is no exaggeration to say that it revealed future possibilities for museums.

(information)

The Citi exhibition Manga

Exhibition period: Thursday, May 23- Monday, August 26, 2019

Venue: The Sainsbury Exhibitions Gallery at the British Museum

Ticket price: Adults £19.50, 16-18 years £16, under 16s free (with a guardian)

*Free for British Museum members

Organizer: The British Museum

https://www.britishmuseum.org

*URL link confirmed on May 1, 2020.