This is a series of interviews with artists who have pioneered the expression of sounds in the world of media arts, including the fields of animation, tokusatsu (special effects), and video games. Our first interviewee is TANAKA Kohei, a unique composer who has been specializing in creating music for animation and video games since the 1980s until today. This year, TANAKA marked the 40th year of his career. In this interview, he fully spoke about his early life, his encounter with animation and video games, and their future as the content industry.

TANAKA Kohei

TANAKA Kohei

Inspired by classical music to become a composer

First of all, please tell us about what made you decide to become a composer.

TANAKA: There is an annual music festival, named Bayreuth Festival, held in summer in Bayreuth, Germany, to perform operas composed by Richard Wagner. It’s a great event adored by classical music fans all over the world, particularly Wagner fans. In 1967, an overseas concert of the festival was held at the Festival Hall in Osaka, where I lived. This concert is one of a very few overseas performances in the festival’s history. I was 13 years old, in the first year of junior high school. I started taking piano lessons when I was a second grader in elementary school and gradually developed a love for classical music. By then, I had become a classical music otaku (freak), asking for a full score of Die Walküre as a birthday present. My parents had no idea why I was so enthusiastic about classical music. I really wanted to go to the concert. It was 50 years ago, but a ticket for the most expensive seat cost as much as 30,000 yen. Even the cheapest seat cost 8,000 yen. My parents weren’t very interested in music, so I tried hard to have them listen to my wish. They finally paid me 8,000 yen to buy a ticket and I was able to go to the concert.

That day’s program was Tristan and Isolte, conducted by Pierre Boulez. I was overwhelmed. It was so great. The performance lasted for four hours and a half and then the curtain call lasted for an hour and a half. No one left during that long time. I kept clapping so hard that my palms were swollen. It changed my life. I started to wish to make moving music like this.

Around the time, an overseas performance of the Bayreuth Festival was beyond expectations, and what’s more, it was given only in Osaka, not in Tokyo. It was a miracle. It’s not too much to say that the performance was given for me to decide my future (laughs). Sometime later, I wrote my impression of that day and sent it to the classical music magazine Ongaku no Tomo. To my surprise, they accepted it and published in the magazine. I received a book voucher worth 10,000 yen as a reward. After deducting the ticket cost, I still had 2,000 yen in my hand. I was victorious (laughs).

You started to study hard to enter the Tokyo University of the Arts’ Department of Composition.

TANAKA: I lived in Osaka with my family, and my father was a doctor there. Being a doctor was his family business for three generations. As I was his only son, he naturally wanted to make me a doctor. In the spring of the year when I became a third-year student in high school, I suddenly told him that I want to become a composer. He was very surprised but said, “I wanted to be a newspaper reporter but became a doctor as my father told me to succeed him. If you really want to be a composer, go ahead.” He also said, “I have one condition. Go to the best school and become the best composer in Japan.” It was an ultimate trade-off (laughs). Anyway, he let me pursue my dream of becoming a composer. I still thank and respect him for having been so tolerant of my wish. My father found me a composition teacher in the Kansai region to go there easily. That’s how I started to prepare for taking the entrance exam of the Tokyo University of the Arts. The teacher also taught NISHIMURA Akira, who is now a leading composer of contemporary music in Japan. Unfortunately, both of us failed the entrance exam in the first year (laughs). To prepare for the exam in the next year, we would go to Tokyo together on every weekend by taking the first Shinkansen train to study with a teacher there and coming back by the last Shinkansen together. We both passed the next year.

Looking back on those days, it’s still surprising that my class at the Tokyo University of the Arts’ Department of Composition was a treasure house of great talents who would later lead the Japanese classical music community. They include composer AOSHIMA Hiroshi; Bach Collegium Japan music director SUZUKI Masaaki; pianist FUJII Kazuoki; MATSUSHITA Isao, who later became president of The Japan Federation of Composers Inc., in addition to NISHIMURA Akira.

I was an inferior student among them. I was the second best on the entrance exam, but second from the bottom when I graduated (laughs). There was a reason. Many classes at the Tokyo University of the Arts’ Department of Composition around that time focused on contemporary music. The entrance exam tested the applicants’ knowledge and abilities in classical and romantic music, but once entering the university, we were always required to write atonal pieces or experimental music. I really didn’t like contemporary music. AOSHIMA and I became rebellious, saying things like, “Why should I do such a thing!” I studied under SATO Shin, who was famous for composing the music for choral works such as Daichi Sansho (Ode to the Earth) and Zao (Mount Zao). I drank with him at a yakitori restaurant near the university every day even in the daytime. It was natural I got poor grades (laughs).

The university’s Faculty of Music did not have a system for finding jobs for graduating students. Faculty of Fine Arts had such a system. I thought it was strange (laughs). When I asked the university office about finding jobs, they were always saying things like, “If you want to be employed by an orchestra, please contact the orchestra directly.” This means that the university left us to rely on our own abilities and “motivation,” in particular, for becoming a music professional after graduation.

You didn’t become a composer right after graduation. You started to work for a record company instead.

TANAKA: Yes. Normally, people would immediately take up a job that they want to do. But I’m from Osaka, a town of commerce, so I’m very cautious about doing a business (laughs). If I suddenly proclaimed, “I’m a composer,” people wouldn’t have given me work soon. For example, it’s not probable a rookie fresh out of university is asked to compose an orchestral piece that involves a big budget. I was aware it’s not that easy. Today, we can make a demo tape by uchikomi, or programming for automatic performance. But there was no such method back then. We had to pay and ask musicians to perform for a demo. It wasn’t easy just to attract people’s attention to our abilities.

I decided to join a record company to experience the music industry for a while, especially its system and inner workings. We can live only one life, so I didn’t want to fail. As the university didn’t find us jobs, I never asked my teachers to write letters of recommendation. Instead, I did a lot of job-hunting activities on my own.

As a result, I was employed by a record company, Victor Music Industries (current-day JVCKenwood Victor Entertainment). Of course, I wanted to be a director in the production department and told it to the company. But on entering the company, I was assigned to the advertising department. I was not happy at first, but I gradually recognized that advertising work is so important and interesting. I was able to be always present in the filming of TV music programs, recording sessions and concerts to watch how they are like. I also traveled across Japan accompanying such singers as SAKURADA Junko, IWASAKI Hiromi, SAIJO Hideki, MATSUZAKI Shigeru, MORI Shinichi, Pink Lady, Southern All Stars, and YAGAMI Junko. I was responsible for some of Victor’s biggest hit artists at the time. I was able to write and read music scores, which is rare for a frontline worker in advertising, so I secretly helped arrange and rework music or scores a little bit at the staff’s request.

By spending my days that way, I learned about the systems of advertising, sales and marketing and how much work and money are necessary to sell one record. I also learned about the nature, customs, positive and negative sides of the industry. People who become a composer on graduation would be confused and say, “My record doesn’t sell. Why?” This is because they don’t know these systems. I think they hardly recognize how much we owe to the fans who buy records and the people at a record company who support these systems. I needed to thoroughly recognize these things through my work. No matter how much my career goes on, I’ll never stop being grateful to these people.

Because of this feeling, I recently started to sell my own CDs at a Comic Market as an ordinary participant. I have 2,000 CDs prepared, bring them to the event venue and sell one by one to visitors, while shaking hands with them. Doing this requires a lot of energy, but I know it is irreplaceable for me. In fact, it makes me feel special when handing one by one to the persons who buy them face to face. I think that getting a job at a record company and being assigned to advertising there eventually contributed to my later life as a big plus. Based on this experience, I always advise young people who want to become composers to “experience various different things and occasions other than composing and doing music before starting to do what you want to do.”

How did you make the transition from a record company employee to a composer?

TANAKA: After about three years with the record company, my father became ill. He said to me from his sickbed, “I gave up on making you a doctor, but it was not to make you a salaried worker. What happened to your plan of becoming a composer?” I thought, “Exactly,” and I started to focus on my original plan. He died without recovering, leaving that comment like a will to me. Two months later, I submitted my resignation to the company. Around that time, I was expanding my network and started to enjoy my work. I gave up all these things and made a fresh start to become a composer.

It was already three years after I graduated from university. I was aware my skills had pretty dropped, so I went to the United States to study jazz at the Berklee College of Music in Boston. I had been so absorbed in the classical music since I was in junior high school that I knew very little about the Western pop music, especially jazz and rock, although I had worked for the Japanese pop music industry.

As an aside, most people in the music industry of my generation were enthusiasts of rock music by The Beatles, the Rolling Stones, Led Zeppelin, and so on. In particular, the presence of The Beatles was so strong that once you were captivated by them, it was hard to get out of their spellbinding power. It’s the same in the animation industry. People who were fans of Uchu Senkan Yamato (Space Battleship Yamato) and Mobile Suit Gundam as children have a hard time getting rid of their influence (laughs). I didn’t experience The Beatles. This would help me a lot later when creating various types of new music for animation and video games.

Your distinctive music background has led you to what you are now. What did you experience when you studied in Boston?

TANAKA: Learning at Berklee College of Music was an eye-opener for me day after day. At the college library, I was able to see handwritten music scores by such great musicians as Thad Jones and Quincy Jones as much as I wanted. As I’m a music score otaku, it was like in heaven. I was amazed at the method of the Western pop music, and at the same time I was able to analyze it much objectively without being absorbed in it more than necessary. This is because I was not influenced by it when I was a child. At the school, I learned good and bad aspects of the jazz theory. It was a precious experience for me. In addition, there was a workshop system at the college. When a composition major wanted to make a demo tape of a music work, instrumentalist students there would help with its recording without fee. In fact, they could learn from the experience, too. I learned various things that would help me work as a composer, from how to write a score of each part to the nuts and bolts of arranging music.

I originally planned to study at Berklee for two years. But I found out I would not be allowed to attend the class that I most wanted to take until I became a third-year student. I went to the student affairs office and said, “I’ve already finished learning the basics at the Tokyo University of the Arts in Japan. Let me skip.” I went there every day and kept shouting, “Too easy for me!” I went there so often that they came to recognize my face (laughs). They finally gave in and allowed me to take the class. Because I joined the class through this irregular process, I’m certain the classmates felt, “There’s a strange Asian guy sitting in the corner. Who’s he?” In return, I got the top grade of A+ in that class to cause them to roar in surprise (laughs). I efficiently took classes that are really necessary for composing music, while skipping jazz piano and other classes, before returning to Japan at the end of my second year.

From advertisement and drama music to animation music

You finally started your career as a composer.

TANAKA: It wasn’t so easy. When I came back to Japan, I didn’t expect to get work orders right away. Instead, I worked as a part-time pianist at a hotel lounge, which was operated by the actress HAMA Yuko. I still remember the actor KATSU Shintaro sometimes dropped in and said to me, “Hi, I’ll sing. Play piano for me.”

After a while, my work network at the record company started to work. The manager of the lyricist ARAKI Toyohisa (*1) at the company said to me, “I’m opening a composers office. Won’t join us?” Nowadays, I belong to a music production company and this person is its president. I started my career there by working as an assistant to an older composer WAKAKUSA Kei (*2).

Sometime later, I started getting orders for writing music for commercials and TV dramas. Music for commercials is strongly influenced by the intentions of client companies. My creations, after working so hard on them, were often rejected easily and I had to rework on them. I was unhappy about this.

I worked on a large number of dramas, starting with TV Asahi network’s Doyo Wide Gekijo (Saturday drama special). A two-hour suspense drama is shot and edited first, before deciding where and when music is necessary in the drama. If the filming takes a longer time, the time for composing music becomes shorter. As I was able to do this only in a day or two, I was convenient for the production staff. In fact, I got many orders. But it was so hard to constantly work under severe time pressure. This is one of the reasons why I almost stopped accepting orders for commercials or live-action dramas later.

Around that time, I was given work on Hoshi no Namida (Tears of Stars), an insert song for the TV animation Waga Seishun no Arcadia: Mugen Kido SSX (Arcadia of My Youth: Endless Orbit SSX) (broadcast 1982–1983), sung by YAMANO Satoko. KIKUCHI Shunsuke (*3), a great master of animation music, composed the music, and I arranged it. That is my first animation song. It was well-received by directors of Nippon Columbia Co. Next, I was given work on the TV animation Kinnikuman (Mr. Muscleman) (1983–1986), a program by another director. I arranged the theme songs for various superheroes, such as Terryman and Ramenman from the animation. I also worked on the tokusatsu special effects program Uchu Keiji Shaider (Space Sheriff Shaider) (1984–1985) at the request of another director, and then Chodenshi Bioman (Super electronic Bioman) (1984–1985). Further, I started to be asked not only to arrange music but also compose music. This is how I built up my career in the animation and tokusatsu special effects fields.

Arranging animation insert songs was a turning point for you.

TANAKA: Around that time, I was approached by NAGATA Morihiro, a music director who had made Cho Jiku Yosai Macross (Super Dimension Fortress Macross) (1982–1983) a huge hit for Victor, which is my former workplace. He had probably acknowledged my work with Nippon Columbia. He asked me to work on the incidental music (or background music, called gekihan or gekiban in Japanese) for the TV animation Yume no Hoshi no Button Nose (Dream Star Button Nose) (1985–1986), as the substitute for the composer scheduled for this work who suddenly became unavailable a week before the recording. It was an urgent and demanding request to write 76 orchestral pieces only in four days. I accepted it on the spot. I quickly made a process schedule. That is, I divided the 76 pieces into four groups to work on every 19 works a day while securing eight hours of sleep without having to pull an all-nighter. As a result, I finished it in three days and a half. I used the remaining time to make a demo tape by an “uchikomi” method of programming for automatic performance. When I brought the demo with the finished works to NAGATA, he was very surprised (laughs).

SASAKI Shiro, who is currently CEO of the animation music production company FlyingDog, Inc., attended their recording. SASAKI used to work for Victor’s sales department, just like me. He was transferred to the production department and his first work there as an assistant to NAGATA was Button Nose. I’ve heard that he was surprised that I wrote 76 works only in four days although I was only a little over 30 years old, and even made a demo tape and conducted at the recording nonchalantly (laughs).

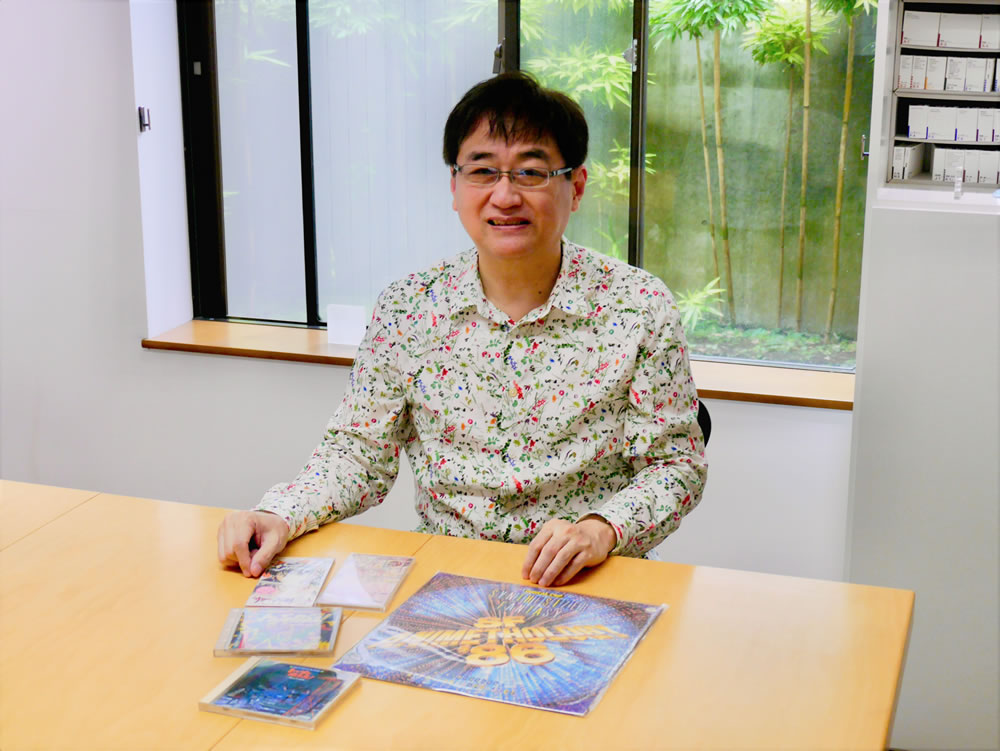

This way, one work was connected to next. My relation with the NAGATA and SASAKI duo led me to work on NHK’s Anime Sanjushi (The Three Musketeers) (1987– 1989), and then the OVA Top wo Nerae! (Gunbuster! aka Aim for the Top!) (1988), for which SASAKI was responsible after being promoted to a director. In the 1990s, SASAKI introduced me to HIROI Oji, who was responsible for the Tengai Makyo (Far East of Eden) and Sakura Taisen (Sakura Wars) video game series. If I hadn’t been confident of writing 76 works in four days for Button Nose and declined the request, my network wouldn’t have developed this much.

I’m always telling young musicians: “You are asked to work on only minor works in the beginning but you should do each work well to present a good result and gain the client’s trust, and continue this process. Doing this is the only way to build up your career. If you are careless or cut corners even only once, you have to start all over again. Once you have a connection with someone or something, you should never let it go. You need to keep it sincerely.

The cover of Top wo Nerae!: Ultra Ongaku Collection The World of TANAKA Kohei (Gunbuster! Ultra Music Collection: The World of TANAKA Kohei) (1996), containing incidental music by TANAKA (above); and an accompanying booklet. Top wo Nerae! (Gunbuster! aka Aim for the Top!) is a story about girls who become pilots of Gunbuster to fight against space monsters.

The cover of Top wo Nerae!: Ultra Ongaku Collection The World of TANAKA Kohei (Gunbuster! Ultra Music Collection: The World of TANAKA Kohei) (1996), containing incidental music by TANAKA (above); and an accompanying booklet. Top wo Nerae! (Gunbuster! aka Aim for the Top!) is a story about girls who become pilots of Gunbuster to fight against space monsters.

As you just said, you had already carried out programming for automatic music performance (called “uchikomi” in Japanese) by yourself around that time.

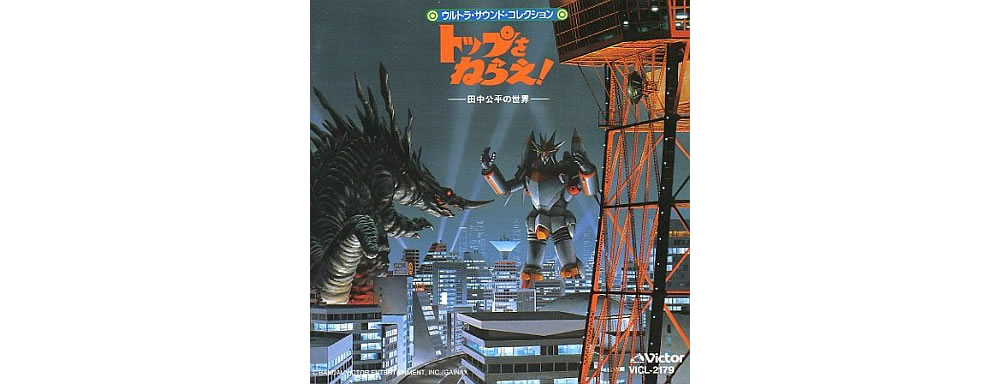

TANAKA: Yes. I’d already made the so-called “uchikomi” music before a normal music sequencer (a programming device for playing music automatically) was available in the market. ARAKI Jun and IWASHITA Tetsuya, who are classmates of mine at the Tokyo University of the Arts’ Department of Composition, developed their original multi-track music programming device by using NEC’s PC-8001mkII (released in 1983). At the time, commercially available sequencers ran automatic performance only in a single track. People usually used this function to overdub and synthesize music. The device made by ARAKI and IWASHITA was already capable of playing multiple electronic music sound sources simultaneously. In order to take advantage of this device, the three of us formed a synthesizer music production team called Appo Sound Project. When I was responsible for arranging the theme song Makafushigi Adventure! (Mystical Adventure!) for the TV animation Dragon Ball (1986–1989), its sound was produced by the Appo Sound Project. I did uchikomi for part of its programming. This song is famous for its very complex music. Actually, the director at Nippon Columbia in charge said to me, “You did too much!” (laughs).

Sometime later, I became too busy working as a composer to participate in the Appo Sound Project’s activities very often. Based at its studio in Mitaka, Appo Sound continued being active in the industry as a synthesizer music production team. Appo Sound produced sound by uchikomi at the Mitaka studio and provided to some of my works, such as the early OVA series Kido Keisatsu Patlabor (Mobile Police Patlabor) (1988–1989) for its theme song Miraiha Lovers (Future Lovers), the OVA Assemble Insert (1989–1990), and Top wo Nerae! (Gunbuster! aka Aim for the Top!) for its insert song Top wo Nerae! Fly High (Gunbuster! Fly High).

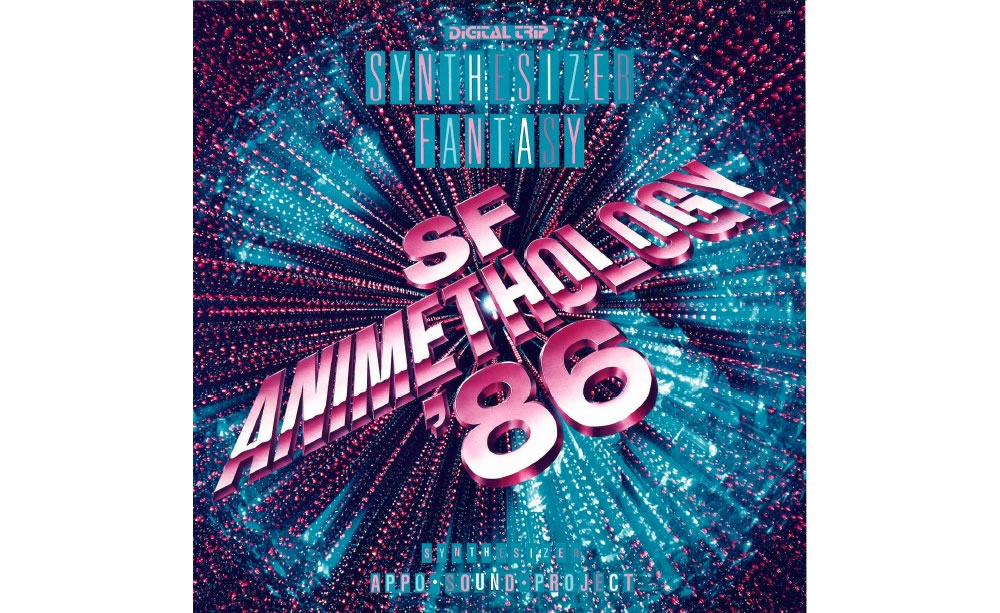

The cover of Appo Sound Project’s SF Animethology ’86 (1986). It contains theme songs and incidental music for such animation as Kido Senshi Z Gundam (Mobile Suit Zeta Gundam), Cho Jiku Yosai Macross: Ai Oboete Imasuka (Super Dimension Fortress Macross: Do You Remember Love?), and Kaze no Tani no Nausicaa (Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind), all arranged with synthesizer.

The cover of Appo Sound Project’s SF Animethology ’86 (1986). It contains theme songs and incidental music for such animation as Kido Senshi Z Gundam (Mobile Suit Zeta Gundam), Cho Jiku Yosai Macross: Ai Oboete Imasuka (Super Dimension Fortress Macross: Do You Remember Love?), and Kaze no Tani no Nausicaa (Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind), all arranged with synthesizer.

(notes)

*1

ARAKI Toyohisa is a lyricist, born in 1943. ARAKI graduated from Nihon University’s College of Art, and made his debut in 1972 with the song Shiki no Uta (Song of four seasons) as its lyricist and composer. His representative works in the fields of animation and tokusatsu special effects include: the theme songs GoShogun Hasshinseyo (GoShogun, take off) and 21Century: Ginga o Koete (21st century: beyond the Galaxy) for Sengoku Majin GoShogun (GoShogun) (1981), the theme songs Love Love Minky Momo and Minky Sutekki Doriminpa for Maho no Princess Minky Momo (Magical Princess Minky Momo) (1982–1983), the theme songs Chojin Sentai Jetman and Kokoro wa Tamago (My heart is like an egg) for Chojin Sentai Jetman (1991–1992), and the theme song Soshite ... Ikinasai (And...you must live) (composed by TANAKA Kohei) for Onihei Hankacho (Onihei) (2017).

*2

WAKAKUSA Kei is a composer and arranger, born in 1949. WAKAKUSA studied jazz theory in WATANABE Sadao’s class at the Yamaha Music Foundation. He studied under composer NAKAYAMA Daizaburo. His representative works in the fields of animation and tokusatsu special effects include: Rokushin Gattai God Mars (Six God Combination God Mars) (1981–1982), Jusenki L-Gaim (Heavy Metal L-Gaim) (1984–1985), Tekken Chinmi (Ironfist Chinmi aka Kung Fu Boy) (1988), Sekai Ninja Sen Jiraiya (World Ninja War Jiraiya) (1988–1989), Tokuso Robo Janperson (Janperson: Fights for Justice aka Special Investigator Robo Janperson) (1993-1994), Romio no Aoi Sora (Romeo’s Blue Skies aka Romeo and the Black Brothers) (1995), Mojako (Mojacko) (1995–1997), and Tomica Hero: Rescue Force (2008–2009).

*3

KIKUCHI Shunsuke is a composer and arranger, born in 1931. KIKUCHI graduated from Nihon University’s College of Art and studied under composer KINOSHITA Chuji. He made his debut as a composer of incidental music for the film Hachininme no Teki (The Eighth Enemy) (1961). His representative works in the fields of animation and tokusatsu special effects include Tiger Mask (1969–1971), Kamen Rider (1971–1973), Shinzo Ningen Casshan (Casshan) (1973–1974), Denjin Zaborger (Electric robot Zaborger) (1974–1975), Getta Robo (Getter Robo) (1974–1975), Doraemon (1979–2005), Dr. Slump Arare-chan (Dr. Slump) (1975), and Dragon Ball (1986–1989).

TANAKA Kohei

Born in 1954 in Osaka. After graduating from Tokyo University of the Arts’ Department of Composition, he worked at Victor Music Industries, Inc. (current- day JVCKenwood Victor Entertainment) for three years. Then, he studied at Berklee College of Music in Boston. After returning to Japan, he began to compose and arrange music in earnest. He worked on music for many popular animation and video games, such as the popular animation ONE PIECE (broadcast on the Fuji TV network) for its background music and opening songs (We Are! and We Go!); and the opening song JoJo: Sono Chi no Sadame (JoJo: His Blood Destiny) for the first season of JoJo no Kimyo na Boken (JoJo’s Bizarre Adventure) (MXTV, etc.). TANAKA also composed music for the video game Sakura Taisen (Sakura Wars), including the theme song Geki! Teikoku Kagekidan (Attack! Imperial Assault Force), better known as Gekitei, which became a huge hit. He has also worked on music for animation adaptations, stage productions, etc., affiliated with the game. He has written music for a total of more than 500 songs. In recent years, he is also active as a singer and music player and gives concerts in Japan and abroad, in addition to composing music. For his music for ONE PIECE, he was awarded with the Animation of the Year Music Prize at the New Tokyo International Animation Fair 21 in 2002. In 2003, he received the Animation Album of the Year at the 17th Japan Gold Disc Awards for his Sakura Taisen 4: Koiseyo Otome––Complete Works Geki! Tei: Final Chapter for Sakura Taisen (Sakura Wars).