Japan’s borders have been closed to tourism for nearly two years now, making social media services and online news reports a lifeline for fans keeping tabs on happenings during the pandemic era. But there’s only so much you can glean secondhand, so let’s take a look beyond the big headlines for some local nuance that people outside of Japan might have missed on the pop-cultural front in 2021 in the fields of manga, music, literature, and film.

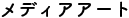

SAITO Takao

SAITO Takao

Copyright © Saito Production

A pair of masters exit the scene

The deaths of two postwar heroes rocked the manga world in 2021. In September, SAITO Takao, creator of the legendary assassin Golgo 13, passed away at the age of 84. Just a month later, the artist SHIRATO Sanpei, famed for Kamui, Ninja Bugeicho (Tales of Ninja Arts), and many other historical epics, died at 89.

Their passing represents the end of an era. For a variety of reasons, little of SAITO’s and SHIRATO’s huge libraries of work have ever made it into English, so their passings got little press abroad. But their names are widely celebrated in Japan, for their unique creations left an indelible mark on the world of manga. In the immediate postwar era of the 1940s and 1950s, manga equated to kids’ fare, as exemplified in the Disney-esque characters and storylines of trailblazer TEZUKA Osamu.

SAITO and SHIRATO were at the vanguard of a new movement in the manga world, fueled by a generation of artists who wrote and drew for teens and young adults rather than kids. Their work helped re-define the potential of illustrated storytelling, pushing manga beyond its origins into a more mature style called “gekiga” – literally “dramatic pictures,” but close in meaning to the English term “graphic novel.” Eschewing cartoony characters for sharply rendered linework, superheroes for antiheroes, lighthearted plots for social criticism, and adding in copious amounts of sex and violence, both SAITO and SHIRATO’s works proved a perfect fit for the socio-political turmoil of the 1960s. SAITO’s stylish assassin-for-hire Duke Togo, codenamed Golgo 13, and SHIRATO’s ninja warrior Kagemaru, from the period hit Ninja Bugeicho (Legends of Ninja Arts), became two of the best-known characters of their era. More than just hits, they became role models for a generation – particularly so for the student protest movement, who saw in these stoic antiheroes allegories for their own struggles against society. Gekiga style proved so compelling and pervasive that it quickly redefined the entire look of comics in Japan. By the end of the 1960s, gekiga style was so ubiquitous that it essentially became the mainstream, even in works actually intended for kids. You can make a case that, artistically speaking, a great deal of the manga consumed around the world today is more accurately described as modern-day “gekiga,” from an artistic, thematic, and audience standpoint. That’s how profoundly the movement affected the manga world, and that’s why the departure of its biggest stars SAITO and SHIRATO in 2021 represents such a loss.

An idol’s triumphant return

TAKEUCHI Mariya’s disco-funk pop tune Plastic Love only sold something like ten thousand copies when it was released in Japan in 1984. By all rights it should have faded into obscurity. Thirty-three years later in 2017, a fan uploaded the track to YouTube, playing over an evocative black and white photo of the singer taken in her prime (*1). Though originally created for a bygone era of discotheques and radio play, the track struck a chord with a totally new generation of online listeners. By 2021 it had racked up more than 55 million views (*2), and sparked an international fad for a bygone genre called “city pop,” a catch-all for Japanese tunes inspired by a mix of imported R&B, fusion jazz, and funk influences that flourished around the bubble era of the 1980s. In its home country, city pop went out of style right around the time the bubble popped in 1990. What brought it back to life – and around the world to boot?

Traditionally, Japanese record labels have resisted exporting their music abroad, perhaps fearing that their content wouldn’t be able to compete against local giants in America and Europe. Ironically, that very reticence may have proven a secret asset, for songs seen as old-fashioned or classic in Japan can feel fresh when discovered by accident abroad. City pop’s influences from Western music mean that foreign listeners can find them both new and somehow familiar at the same time. It’s also driven by what might be called pseudo-nostalgia: generations of kids raised on Japanese video games have essentially been consuming city pop without even realizing it, in the form of classic video game soundtracks inspired by city pop and city pop’s own influences.

TAKEUCHI’s surprise revival may have finally prodded Japanese producers to start thinking more outside of the confines of Japan. In 2019, Warner Japan released an all-new video for Plastic Love. Then, in November of 2021, they authorized the pressing of a new 12” record of the single featuring the very same photo used in the YouTube upload that started it all, bringing the fad back around full circle (*3).

AKEUCHI Mariya, Plastic Love (Official Music Video)

The full version of a new music video that was produced in 2019.

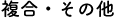

A strange writer’s strange comeback

The novelist DAZAI Osamu died in 1948 at the age of 38. His short, turbulent life was marked by struggles with illness, depression, and addiction, but his intensely personal, existentialist novels drew in many Japanese readers during the pre- and postwar eras. No Longer Human, published the year of his death, portrays the life of a self-destructive antihero who slowly descends into madness, taking a string of lovers with him. The thinly-disguised self-portrait of the artist launched a “Dazai Boom” in the late 1940s that continues in many ways today.

DAZAI Osamu in February 1948. Photo by TAMURA Shigeru.

DAZAI Osamu in February 1948. Photo by TAMURA Shigeru.

No Longer Human is the second best-selling Japanese novel in its home country, but even after receiving multiple English translations (most recently Mark GIBEAU’s, retitled A Shameful Life,) DAZAI’s work has more or less languished in obscurity abroad, aside from academics and deep fans of Japanese literature.

That all changed in 2021. The hashtag #dazaiosamu began trending on TikTok; videos featuring it have been viewed 2.1 billion times as of this writing in February 2022. As a result, translations of No Longer Human shot up the Amazon bestseller lists: a real feat for an author who’s been dead for nearly seventy years.

One reason for the recent surge in interest may be the cult popularity of the animation series Bungo Stray Dogs, which re-envisions Japan’s prewar literary scene as a supernatural detective drama. Originally aired in Japan starting in 2016, it appeared on the animation streaming service Crunchyroll in early 2021, re-introducing it to new fans abroad. A stylized portrayal of DAZAI plays a major role, and the character’s nihilistically detached demeanor seems to be resonating with animation lovers around the world, sparking a renaissance in interest for the real-life author’s works. Perhaps once Japan reopens to visitors, some might seek out the Dazai Osamu Literary Salon in the author’s old stomping grounds of Mitaka, Tokyo to learn more about the man behind their hero.

The End of a Legend

The 2021 release of director ANNO Hideaki’s animation film Evangelion: 3.0+1.0 Thrice Upon a Time brought the Evangelion series to a conclusion nearly a quarter century after the original television show first aired. It proved a huge hit, domestically and abroad, and satisfyingly concluded the long-running series through decades of twists, turns, and retellings. But Evangelion’s conclusion represents more than just the coda to a beloved animation franchise – it’s arguably the climax of an entire social movement.

When the animation series Neon Genesis Evangelion, debuted in the fall of 1995, Japan’s pop cultural scene was a much different place than it is today. Society at large regarded animation as kids’ stuff, and anyone beyond that demographic who consumed it was disparaged as an “otaku,” meaning someone in a state of arrested development, clinging to childish pastimes as an escape from reality. In fact, when Neon Genesis Evangelion first aired on Japanese television, it was as the replacement for a Japanese-dubbed version of the American kids’ cartoon Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. Few realized just how profoundly transformative the show might be.

But as word began to spread of this intricately plotted and animated new series, filled with homages to classic live-action and animated shows, it grew into something more than another cartoon. At first it was a cult hit, then, after the last episode aired on a conceptual cliffhanger, it exploded into a society-wide phenomenon. Japan’s young people were struggling through the first of what would be two “lost decades” of economic precariousness, social problems, and political stagnation. As safety nets like lifetime employment evaporated, so too did hopes for a comfortable adulthood. Evangelion centered on the struggles of IKARI Shinji, an introverted young boy forced by grown-ups into an existential conflict with no regard for his physical or mental health. In his predicament, it seems, many young Japanese saw a reflection of their own.

The theatrical edition, released two years later, went on to win the Japan Academy Film Prize for “Most Talked-About Film of the Year.” Evangelion’s huge success, not simply among animation fans but society at large, almost singlehandedly reversed the long-standing misconception of animation fans as social dropouts. Suddenly it was okay, even a little hip, to admit to liking animation, no matter if you were a teen or an adult. A huge number of imitators and rivals followed, transforming the image of animation both in Japan, and abroad when it began to be exported in large numbers around this time. Today, it isn’t at all odd for grown-ups to revel in what would have been considered kid stuff by earlier generations, whether video games, superhero movies, or animation itself. Evangelion was key to that global shift in our fantasy lives. Its subtitle is “Neon Genesis” in English, but the Japanese is Shinseiki, “New Century.” It’s a prescient phrase, for it is entirely possible that without it, the 21st century boom for animation around the globe never would have happened.

In celebration of this and his other many creations, the National Art Center Tokyo held a Hideaki Anno Exhibition from October 1 through December 19, 2021. Following his trajectory from an obsessive fan into one of Japan’s most respected creators, it was filled with original art from the Evangelion series and ephemera from his personal collection, proving that pop culture is about more than entertainment – it has the power to transform people and society both.

(notes)

*1

Cat ZHANG, “The Endless Life Cycle of Japanese City Pop,” Pitchfork, February 24, 2021.

https://pitchfork.com/features/article/the-endless-life-cycle-of-japanese-city-pop/

*3

Jake SIBERT, “THE CATCHY JAPANESE POP SONG THAT DOMINATES YOUR YOUTUBE RECS IS BACK!,” HIGHSNOBIETY.

https://www.highsnobiety.com/p/plastic-love-reissue/

*URL links were confirmed on February 3, 2022.