What has changed most since the 1990s is probably the relationship between works and viewers. In “The Death of the Author” (1967), Roland BARTHES argues that a work is no longer dictated by the author and posits, in its wake, “the birth of the reader.” Technology has encouraged and tested viewers and users’ active involvement. That can be what has changed in the media environment for the past 10 years. This article will explore the imagination developed by media art about other people you do not meet in person, together with the historical background.

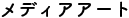

Light on the Net on exhibit in the entrance of Softopia Japan Center building (1999).

Light on the Net on exhibit in the entrance of Softopia Japan Center building (1999).

Taken from a 120x speed video of the exhibit at the Gifu Ogaki Biennale 2017.

In media art, the media consciousness and environment that connected the artist and the viewer when the work was first presented does not last and is often lost. Contained in that loss is the issue (or possibility) of recollection, which could affect the reinterpretation of the work’s identity in the future. Media art always entails those questions. From the reproduction of Light on the Net by FUJIHATA Masaki, which was first exhibited in 1996 when the Internet began to spread, this article discusses the intention of the work and its present significance.

I choose to use the term “media art” among all the forms of artistic expression because I intend to focus on the imagination projected achieved by means of infrastructure related to network and media technologies. Particularly Light on the Net, I believe, is a work we should review now in that the work provides a remote experience of it via the Internet and reminds us of a prototype of social media.

A work based on media technology of a certain era, even if the work is relatively new, can become hard to reexhibit due to technical conditions or the original meaning can be altered as technology changes. At the same time, moves are afoot to appreciate environmental changes or social significance of past works that the creators didn’t necessarily see at the time of production. For example, the New Museum of Contemporary Art in the United States began to collect works of Internet art as browser images in 2016. In other words, it can be said that media art will be reinterpreted using archival materials besides the works themselves. This way, “reproduction” leads to such discoveries. The themes of the Gifu Ogaki Biennale 2017 held at the Institute of Advanced Media Arts and Sciences (IAMAS) were the restaging, reproduction and reexhibition of media art.

Re-performing, reproducing, and re-exhibiting media art

The Gifu Ogaki Biennale was first held in 2004. The year 2019 marked the eighth event. In 2017, which marked the 21st anniversary of the foundation of the IAMAS, My colleague MATSUI Shigeru and I organized an exhibition of archival materials for the consideration of media art research and a 6-day symposium, under the title “The New Era – the Dawn of Media Art Studies.”

Exhibition of archives at IAMAS library

Exhibition of archives at IAMAS library

A scene from the symposium, (from left to right) KUBOTA Akihiro, FUJIHATA Masaki, and MIWA Masahiro

A scene from the symposium, (from left to right) KUBOTA Akihiro, FUJIHATA Masaki, and MIWA Masahiro

This event was planned to find out the identities of works created more than 10 years before by studying various archival materials and performing emulation (*1). Our intention was to think of how the identity of a work could be determined and passed down to future generations after the consciousness of medium and the production environment that connected the artist and viewers when the work was first exhibited were lost. The point of discussion was how we should take the description, recording and storage of works by KUBOTA Akihiro with an engineering background, MIWA Masahiro with a musical background and FUJIHATA Masaki with an artistic background.

Engineering, Music, and Art:

Different Views on Reproduction

What appeared through the discussion with KUBOTA was his proposal to update the concept of a work. KUBOTA’s exhibit was a work using a program code. Poems, images and music were displayed separately on three monitors. The core of the work was the “value in implementation” of a program. Texts, images and sounds were generated according to their surroundings and that was the key feature of the work. KUBOTA defined the work as a “prototype.” He proposed disclosing the code on a software development platform GitHub not only to manage versions but also to make the code publicly available. According to KUBOTA, a work keeps changing and something different is generated every time. The essence of a work is the code. His point is to let anyone see the code or even create a derivative work from the code. This view of his suggests an attitude of trying to redefine more broadly a creator’s characteristic signature and the uniqueness of a work, which have been taken for granted in the conventional concept of art. In the future, the beauty inherent in a code will have to be debated. Following his view, we incorporated codes, sound sources, photographic and video records of KUBOTA’s live coding works from 2005 to 2009 into existing archive software and exhibited them.

The exhibit by KUBOTA (IAMAS library). Images were generated in response to the surroundings.

The exhibit by KUBOTA (IAMAS library). Images were generated in response to the surroundings.

Codes, sound sources, photographic and video records of live coding works were exhibited.

Codes, sound sources, photographic and video records of live coding works were exhibited.

Music, particularly musical performance, is premised on the assumption that it is to be performed again. It is natural in the world of music that a score written hundreds of years ago is played and appreciated and that its interpretation is studied. Nevertheless, re-performing in works of MIWA Masahiro often provoke debate. One possible reason is that his musical work includes the device used for the performance and therefore a work to be re-performed also includes the device. This is a common problem to all the live electronics works. At the Gifu Ogaki Biennale 2017, a piece for computer and harp Trödelmarkt der Träume = Yume no garakuta-shi: Vorspiel und Lied (1990) was performed by the same harpist twice in a version with the original system configuration and in an emulated 2009 version. As to the performance, the harpist played an actual harp while singing and the computer generated the performance data in real time. The sounds of the two harps were combined with sampled everyday sound, such as street noise and children’s voices, played and controlled by a computer program. For the computer system, the Atari ST computer and the AKAI S1000 sampler were used in the original production. In the 2009 version, the STEEM emulator running on the Windows and the Native Instruments’ KONTAKT software sampler were used. The purpose of emulation is to ensure that the music can be played even if the original equipment is broken or unavailable. However, a question may arise whether the reproduction maintains the identity of the original work.

SHINOZAKI Ayako, harpist, playing Trödelmarkt der Träume and MIWA

SHINOZAKI Ayako, harpist, playing Trödelmarkt der Träume and MIWA

For example, due to the characteristics of the software, the sound is subtly different from that of the original device. There is some debate over whether such a difference should be allowed as part of the interpretation. In the composer MIWA’s view, the difference was considered not a problem when compared with the interpretation and performance from the perspective of music. However, it could be presumed that accidentalness caused by the computer which had been intended when the music had been composed included otherness like the one expected from AI nowadays. It is deduced that the accidentalness brought by the otherness became the object of evaluation and gave the performer a sense of tension in some aspects. Such interpretation is important in thinking about the significance the work has first had. It should be supplemented by the critical imagination of the interpreting person and passed down.

Finally, the discussion with FUJIHATA Masaki centered on Light on the Net exhibited on the first floor of the Softopia Japan Center building, which is used as campus of the IAMAS now. Prior to the exhibition, FUJIHATA had Anarchive No.6: FUJIHATA Masaki (Anarchive, Paris, 2016) published by a French publisher invited by Anne-Marie Duguet, an art researcher and curator. This series of publication featured Antonio Muntadas (1999) first, followed by Michael Snow (2002), Thierry Kuntzel (2007), Jean Otth (2007), NAKAYA Fujiko (2012) and recently Peter Campus (2017). The publications attempt to create an archive in the form that matches each artist’s distinctive characteristics of expression. The volume on FUJIHATA cover almost all his works, including the experiments providing spatial experience of various works by means of AR (augmented reality), together with research papers on his early works in the 80s. The book is said to be a valuable archival material that shows the systems of works that could not be experienced directly. In the Gifu Ogaki Biennale 2017, we proposed reviewing and reconstructing Light on the Net using archives only without recreating the interactive elements of the work.

The Public Sphere Imagined in Light on the Net

First, I would like to look at what Light on the Net was like in detail because I consider Light on the Net a particularly symbolic work in thinking of art in the era of information technology.

Light on the Net was a joint research project by FUJIHATA Masaki’s laboratory at Keio University and Softopia Japan. The work consisted of a website and a structure installed in the entrance of the Softopia Japan Center building. Viewers could access the website and see the image of light bulbs on the 7×7 grid structure installed in the entrance of the Softopia Japan Center building. When a viewer hovered the mouse pointer over a light bulb on the screen, a hand icon appeared. The viewer could click the icon to turn on the light or turn it off if the light had been on. Because the streaming technology was not available yet, after the viewer turned on a light on the screen and the light came on, the grid was photographed and sent to the viewer. That took 4 seconds and it required 10 to 15 seconds all together to complete the operation of the whole grid as the Internet was not as fast as it is today. This mechanism was reflected in the grid installed in the Softopia Japan Center building and visitors to the venue could see the lights switched on and off in person.

Light on the Net reexhibited. The 7×7 grid and a video created from website images and the access log were exhibited.

Light on the Net reexhibited. The 7×7 grid and a video created from website images and the access log were exhibited.

Interestingly, the work was premised on communication on the web although it could be also seen on the venue. The image below displays an access log of 10 actions. As the log contains IP addresses and domain names, it shows which light was switched on when and where. At the Gifu Ogaki Biennale 2017, FUJIHATA showed a video of the lights coming on and going out at 120 times speed using the images and the access log left on the server used for the original work. He aimed at showing what quality of communication was occurring when people across the world could watch the same image and access the switches to turn the lights on and off.

In the original project, the website displayed the image of the grid and an access log of the last 10 actions.

In the original project, the website displayed the image of the grid and an access log of the last 10 actions.

Video played at 120 times speed

What the video suggested was an early version communication on the Internet. For example, someone turned on the lights in the shape of a heart every morning. One day, someone else tried to write letters HI on the grid. Another person joined. It was not clear whether the second person wanted to help the first person write the letters. The first person tried to write HI again. A third person accessed and deformed the letters. Those people fought for the switch. The first person tried to restore HI. Finally, yet another person switched off all the lights and seemed satisfied. The video showed that people meeting one another for the first time on the website felt the presence of one another, guessed others’ intentions and formed a consensus.

What quality of communication was occurring then? Firstly, what was made possible by displaying symbols and letters by switching on or off the lights on the 7×7 grid was limited to communication with simple shapes and words. Secondly, as explained above, it took 10 to 15 seconds to complete the operation of the grid after a command to switch on a first light was sent. If several people accessed the website simultaneously, they had to send a command while feeling the presence of others. In other words, viewers were tested how they would make the most of that very limited function they were given for the first time.

Afterwards, communications services, such as blog, message board and social media, have emerged as we know very well and they are now part of everyday life. Particularly since 2007, the form of communication has drastically changed due to the wide spread of smartphone and social media. The Internet is no longer a virtual reality. The world has shifted to a connected society. Looking back, however, Light on the Net was heading in a different direction from the current development and we should pay attention to that.

When thinking of a community created by the Internet, people may recall “global village” popularized by Marshall McLuhan as the first ideal community. McLuhan predicted that national and tribal borders would mean nothing and the world would become one global and universal community like a village. However, McLuhan said “The more you create village conditions, the more discontinuity and division and diversity. The global village absolutely insures maximal disagreement on all points. It never occurred to me that uniformity and tranquility were the properties of the global village. It has more spite and envy (*2).” As OSAWA Masachi pointed out in “Electronic media community,” quoting the concept of “long-distance nationalism” introduced by Benedict Anderson, it’s true that communication on the Internet evoked new nationalism all through the 90s (*3). In other words, such communication as utmost immediacy and local consensus formation make up the core of the identity of an individual was emerging. If we think again in that context about what Light on the Net presented, it can be said that the work directly questioned viewers/users about the nature of a public sphere based on information technology.

What has become clear from the reproduction of Light on the Net is a question as to what a new public sphere brought by information technology is. That is also a question of how art can develop imagination about others you have never met. I believe, a question of how to design the interaction between people is the very issue raised by media art, which expresses imagination by means of infrastructure related to network and media technologies.

(notes)

*1

Emulation is the process of imitating the behavior of a device, software or a system on another software program to run the program instead of operating the device, software or system.

*2

G. E. STEARN ed., McLuhan: Hot and Cool (The Dial Press, New York, 1967) 272.

*3

“Electronic media community” by OSAWA Masachi, “Globalization of media hybridity and borderless multicultural society” by YOSHIMI Shunya, OSAWA Masachi, KOMORI Yoichi, TAJIMA Junko, YAMANAKA Hayato (Seikyusha, 1999), 49–51 and 92–93.