This is the fourth installment of a series of interviews with editors of manga magazines, focusing on the past and the future of the genre. This installment will feature Masahiko Ibaraki, a former head editor of Shukan Shonen Jump weekly boy’s magazine, once again following No. 3 to learn about strategies to make a magazine attractive for a wide range of people.

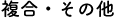

The cover of a reprinted edition of the Shukan Shonen Jump’s third and fourth combined New Year issue for 1995, which printed a record 6.53 million copies

The cover of a reprinted edition of the Shukan Shonen Jump’s third and fourth combined New Year issue for 1995, which printed a record 6.53 million copies

© Shukan Shonen Jump third and fourth combined issue for 1995 / Shueisha Inc.

Making an orthodox boys’ magazine despite many female readers

This second part will examine the driving force of the magazine’s remarkable success a little more in detail.

In the late 1980s, Shukan Shonen Jump weekly boy’s manga magazine started to attract a wide range of readers. In the 1970s, most of the readership were boys in elementary and junior high schools. Since the mid-1980s, the magazine started to have more and more adult readers. Particularly, the magazine steadily increased female readers. I asked Ibaraki about whether the magazine’s editorial department had any secret strategy to attract female readers.

“No, we didn’t. We noticed the magazine started to gain female readers when we were publishing ‘Saint Seiya’ (published in the magazine in 1986-90) by Masami Kurumada. But we didn’t intend to target female readers. We were always faithful to the firm policy of making a magazine for boys as this is a boys’ magazine. We don’t mean to exclude female readers, but targeting women isn’t our style. Women who like manga of Shukan Shonen Jump have probably found something they can relate to in the content meant to attract boys, find their favorite characters there, and enjoy doing these things. I suppose they must be disappointed if the magazine shifts to target women. It’s true we had female protagonists in Tsukasa Hojo’s ‘Cat’s Eye’ (1981-84), but this work couldn’t possibly aim to attract women as its editor in charge was [Nobuhiko] Horie, who was also editor in charge of ‘Fist of the North Star’ (laugh). The drawings of ‘Cat’s Eye’ were very novel, comparing with conventional drawings of Jump. I’d felt Jump’s drawings were becoming refined while Toriyama and Katsura started to serialize their works around that time. I enjoyed reading Shukan Shonen Sunday and Shukan Shonen Magazine when I was a child. On the other hand, I didn’t like Jump’s drawings as they looked cluttered or messy, to be honest (laugh). I still didn’t read Jump when I was in college... It was only by chance that our magazine started to have manga creators whose drawings are fine, not by an editorial strategy. This also contributed to attracting female readers as a result, I suppose.”

Fruits of training new gag manga creators

Featuring interesting gag manga was an advantage of Shukan Shonen Jump over its competitors around that time.

Earlier, Shukan Shonen Sunday similarly increased its readership thanks to “Osomatsu-kun” (1962-69) by Fujio Akatsuka and “Obake no Q-taro (Q-taro, the mischievous ghost)” (1964-66) by Fujio Fujiko, while Shukan Shonen Champion rose to the top due to “Gakideka” by Tatsuhiko Yamagami and “Macaroni Horenso” by Tsubame Kamogawa. These successes prove that weekly boys’ magazines with interesting gag manga can attract readers.

Shukan Shonen Jump constantly published four or so gag manga hits, such as publishing “Kochira Katsushika-ku Kamearikoen-mae Hashutsujo (This is the police box in front of Kameari Park in Katsushika Ward” by Osamu Akimoto, which is a regular fourth batter; “Jungle King Tar-chan” (1988-90) by Masaya Tokuhiro; and “Tsuide ni Tonchinkan” (1984, 85-89) by Koichi Endo all together. The magazine also had new gag manga creators make their debut one after another.

“As an editor in charge of gag manga, I received an in-house award named Shueisha award. My award certificate reads, ‘Your sense of gag is exceptional...’ (laugh). I just discovered manga creators who can create funny works. Jump’s mainstream is always manga like ‘Fist of the North Star’ and ‘Dragon Ball.’ Gag manga are merely a kind of supporting players. In this respect, it may be very unusual that we had an award aimed for discovering good supporting players. We already had the Tezuka Award and the Akatsuka Award, and in 1989, I set up an award named Gag King (continued 1989-97). We generously offered 500,000 yen in prize money and a guarantee that winners’ works would be published in our weekly magazine. As a result, we attracted a huge number of entrants. Among these entrants was Gataro Man, who won the first Gag King award. We also published extra issues exclusive for gag manga. We put great emphasis on gag manga, as a matter of fact.”

Around that time, it was very unusual to make a pledge to publish rookies’ work in a regular issue or publish extra issues exclusively featuring works of budding manga creators.

“Since [Jump] was sold best in Japan, many young manga creators were motivated to create for our magazine, I suppose. In addition, due to the magazine’s good sales, the editorial staff were also allowed to do whatever we wanted to do. These circumstances had a great combined effect of attracting the cream of aspiring manga creators, I suppose. But with regard to gag manga, only a small number of volumes in comic book form were published and their printed copies weren’t so many. Despite the situation, I was acknowledged as a gag manga editor. I was a bit of a maverick in my workplace and felt out of place a little, so I was very happy when Masanori Morita’s ‘Rokudenashi Blues’ (1988-97) became a hit as I was his editor.”

Finally exceeded 6.5 million copies

In 1990, “Slam Dunk” (1990-96) by Takehiko Inoue and “Yu Yu Hakusho” (1990-94) by Yoshihiro Togashi started to be serialized among other works. Jump’s printed copies exceeded the 6 million mark in its third and fourth combined issue of 1991, recording 6.02 million. The number made headlines as the magazine surpassed The Yomiuri Shimbun, a national daily having the largest readership in the genre. In 1993, the year Jump marked its 25th anniversary, a commemorative event titled Jump Multi World was held at the Prism Hall of the Tokyo Dome City in Bunkyo Ward, Tokyo, from July 28 to Aug. 15, attracting 160,000 people. To print 6 million copies every week, Kyodo Printing Co., Ltd. built a new printing factory for Jump in the town of Goka, Ibaraki Prefecture. This also made headlines.

“The last issue of 1994 marked a record 6.53 million copies, but we weren’t hardly aware of this. The head editor must have been aware, but we were always so busy dealing with tasks at hand that we didn’t have time to pay attention to other matters, as I’ve told you many times. When Kyodo Printing’s new factory was completed, we were invited to see it by the printing company’s official in charge. But we didn’t make it as we were very busy. I wonder why Jump sold that well. When the printing reached 6 million, the editorial department prepared and gave commemorative gifts to the staff, as long as I remember. But there was no celebration by Shueisha on the company level. After all, Shueisha’s main business focus in that era was women’s magazines and girls’ manga magazines. We remained only a supporting player. The time has changed and we now have president who is from Jump and many board members also from Jump. But under the company culture around that time, we felt we shouldn’t be openly proud of achieving 6 million copies.”

Amid the favorable business conditions of the bubble economy in the late 1980s, women’s fashion magazines and information magazines for young adults made big gains by advertising revenues alone. On the other hand, manga magazines were priced at several hundred yen per copy, putting them in reach of children. In addition, space to run advertisement was limited to their covers, several pages in the front section and color pages.

At that time, boys’ magazines were not a big focus for Shueisha, as they weren’t expected to reap advertising revenues. However, that may have given the staff at Jump the chance to work with greater freedom. Manga in the magazine form and in the comic book form finally came under the spotlight after the publishing business experienced a downturn and advertising revenues started to decline.

Jump editors lead media mix

Shukan Shonen Jump produced significant results in media mix, too.

“Fist of the North Star,” “Dragon Ball,” “Jungle King Tar-chan,” “Slam Dunk,” and many more were made into TV anime and game one after another, all becoming hits. People who came to like these anime works have become new fans of magazines and comic books, thus creating a long-lasting virtuous cycle.

“Manga works that were made into anime thrived very much around that time. They are still thriving today, but have less momentum. It may be because there are fewer people who read original manga after watching their anime adaptation. We had offers by various different businesses for making anime adaptation and video games based on Jump manga. We still have such offers today. Unlike today, our company had no department for rights business, so the editorial department handled those offers at its own discretion. Of course, our company had a section like a predecessor of today’s rights business department to properly deal with contract matters on behalf of us. But basically, our department made its own decisions. I did so, too, at my own discretion in a way, when I was in the department. When I was head editor of Jump Square (a monthly manga magazine), anime adaptation of “Blue Exorcist” (2009-) by Kazue Kato was decided at a party somewhere. An official of Aniplex Inc. anime production company I met there suggested making a TV anime adaptation of this work by saying, ‘There’s a vacant slot on TBS. Won’t you do it with us?’ We reached agreement only in 10 seconds or so. Making a contract could be discussed later. When I was transferred to the rights business department, its authorities were becoming larger, in contrast. If editors do such things today, I would complain as I’m in charge of rights business.”

It is manga editors who work with manga creators on a regular basis that know and understand manga most, so this may have been a right way of thinking.

“About requirements for anime adaptation, there is one thing to meet. We should select manga that has been serialized for at least two years. If it has lasted for two years, eight or so volumes in the comic book form have already been published and we have enough episodes. Two years’ serialization also proves that the manga work is very popular, so its anime can get high audience rates and its sponsors won’t be troubled. If anime works get high audience rates, the original manga books can sell well as a result. Being serialized for two years became almost an unwritten condition, although it wasn’t a clear rule. In contrast, we have to decide at an earlier stage today as the schedules of anime production companies are full up to two years later. In addition, hit manga works are fewer than before, so anime adaptation tends to be concentrated on a single manga work. There’s one more remarkable change. Both editors and manga creators know about anime much more than before and their top priority is anime’s quality. Speaking from my current post, I’m more grateful for anime being broadcast for long periods of time.”

Most memorable manga creator

Before finishing this interview, I asked Ibaraki about the most memorable manga creator during the decade in the magazine’s heyday.

“Personally, I feel like saying it’s Masanori Morita, but nevertheless, I should say it’s Akira Toriyama. His manga’s anime is still as popular as ever. He has had a great influence on younger manga creators, too. Eiichiro Oda and Masashi Kishimoto admired Toriyama so much that they decided to become manga creators themselves. It’s not too much to say that Toriyama was a driving force for boosting Shukan Shonen Jump with his influence above and beyond his manga works.”

Looking at the current situation from a different viewpoint, absence of charismatic manga creators with immense popularity and influence may have caused the stagnation of today’s manga circles.

Masahiko Ibaraki

Born in 1957, Ibaraki was assigned to the editorial department of Shukan Shonen Jump weekly boys’ manga magazine in 1982. He served the magazine’s eighth head editor. He also served founding head editor of Jump Square. He is currently in the posts of managing director of Shueisha Inc. and director of Shogakukan-Shueisha Productions Co., Ltd.

*Data on the numbers of printed copies provided by the editorial department