This is a series of interviews with artists who have pioneered the expression of sounds in the world of media arts, including the fields of animation, tokusatsu (special effects), and video games. This time, we interviewed KOSAKI Satoru, who marked the 20th anniversary of his debut in 2020. KOSAKI started his career as a sound creator for a game maker, and later became a composer. Since then, he has created music for blockbuster animation one after another, becoming one of the leading composers of animation songs and incidental music in the 2000s and 2010s. He spoke in detail in an informative manner about various topics, such as secret episodes about creating great hit animation songs and his composition techniques using sounds by music programming (called desktop music or DTM in Japan), a characteristic method used by his generation.

KOSAKI Satoru

KOSAKI Satoru

Photos: HATAKENAKA Aya (all photos in this article)

Encounters with music, animation and video games

Please tell us about your first encounter with music when you were a child.

KOSAKI: First of all, I started attending an infant course at Yamaha Music School when I was three. I took lessons in rhythm expression, music pitch training and playing the piano and electric organ. I don’t remember much, but I hear that I myself said I wanted to go there. I was only three, so I don’t know why I wanted to go to a music school. It’s probably because I was influenced by TV animation and puppet plays. I especially liked NHK’s Purin Monogatari (Story of Princess Purin Purin) (1979–1982). My parents were not music professionals, but they played the classical guitar. Records of the famous classical guitarist Narciso YEPES, for example, were played on a daily basis at home. My parents played music themselves, too. They also seemed to like baroque music. Of course, Japanese pop songs were also played. My mother liked The Checkers and Anzen Chitai. She often sang their songs while doing housework. So I was already able to play the piano when I was a child, but I didn’t have an idea of becoming a musician. I stopped taking lessons once when I was in the fifth grade. First of all, I hated practicing. Each time I went to class, I was always scolded (laughs).

What kind of animation or video games did watch or play as a child?

KOSAKI: About animation, I was very impressed by NHK’s early evening programs such as Spoon Obasan (Mrs. Pepper Pot) (1983–1984). I also liked Dr. Slump Arale-chan (1981–1986), Meitantei Holmes (Sherlock Hound) (1984–1985), and other programs that many children would usually watch. About video games, my father had an NEC PC-9801 (released in 1982), so I started playing simple PC games such as pinball when I was still very young. I also played golf games and flight simulation games on my own, even though I didn’t understand them well. I further played role-playing games somehow, such as Xanadu (1985), even though the menu screen was in English and I didn’t understand any of it. At friends’ homes, I naturally played Pyuta (Tomy Tutor) by Tomy Company, Ltd. (currently known as Takara Tomy in Japan) and Family Computer by Nintendo Co., Ltd. I think the first Family Computer software my parents bought for me was probably Dragon Quest II: Akuryo no Kamigami (Dragon Quest II: Luminaries of the Legendary Line) (1987).

Did you do any musical activities in junior high and senior high schools?

KOSAKI: I stopped taking piano lessons, but my interest in music did not fade. I joined the brass band club in junior high school and senior high school and played the trumpet. I don’t really remember why I chose to play the trumpet... It is maybe because it was flashy and I liked it, or maybe an older club member told me to do so. When I joined the club, I even didn’t know well what kind of instruments are used in a brass band. Two years later, I finally realized that the trumpet’s C is different from the piano’s C (laughs).

By that time, I had started to listen to the types of music I like, but my choices were diverse. First, I was attracted to fusion music such as Casiopea (currently Casiopea 3rd) and The Square (currently T-Square). As I played musical instruments, I liked bands that played technically sophisticated, instrumental music. I also listened to Japanese pop music such as TM Network and Kome Kome Club, which were popular at the time. Also, I loved MINAMINO Yoko since I was in elementary school, admiring her powerful but melancholic songs. I especially liked their music arranged by HAGITA Mitsuo. That was probably the first time I became aware of the job of arranging music. I often listened to Hikaru Genji, which boys do not listen to very much, as I noticed they had great arrangements with a lot of synthesizer sounds. I think I was more attracted to the systematic, well-constructed sounds rather than songs by singer-songwriters playing accompanying music by themselves.

I was also interested in music for video games. As I said earlier, there was a PC-9801 at home, and I was interested in the way of creating music by programming. My father subscribed to a monthly computer magazine Mycom BASIC Magazine. As each issue featured a game music program, I would input the program to let it play. I even put my ears on the casing of a speaker at a game center to hear more clearly (laughs). But actually, I rarely thought of myself becoming a creator up until I finished high school.

Starts composing music in a dojin composition circle

So, when did you start thinking about creating music?

KOSAKI: I was good at math and not good at classical Japanese and Chinese literature. What’s more, I was very interested in cognitive science related to human vision and hearing, so I entered Kyoto University to study at the Faculty of Engineering’s School of Information Science. I joined a brass band at the university as I wanted to continue playing music. When looking around to find how other circles are like, I got interested in a circle called Yoshida Ongaku Seisakujo (Yoshida Music Works), which was a kind of light music club for original music only. It was similar to what we would call a dojin composition circle today. I went to their welcome concert for new students, which featured a wide variety of music there, including a band playing my favorite fusion, a techno unit like P-Model, and a performance incorporating theatrical elements. I experienced so many types of music that I had never heard before all at once. I was very surprised that they were created by people who were about my age. So I cancelled joining the brass band and joined that club instead, even though I had never made music on my own. At that time, at most of the light music clubs, new members started with cover bands with members playing together and placing greatest importance on the Western pop music. On the other hand, the circle was limited to self-composed music, and its members were science-oriented people who liked making things fanatically. In a word, the circle suited me very much.

When I entered university, I was given a Roland JV-1000 synthesizer (released in 1993) combining a sound source with a sequencer (a programming device that automatically plays music). For the first time, I had an environment for making music by “uchikomi” (programming for automatic performance). I added a four-channel multi-track recorder (MTR) for cassette tapes before joining the activities of the composition circle. It was around at the dawn of consumer products that are capable of creating what is now called DTM (or desktop music) at reasonable quality. But as I mentioned earlier, the circle did a wide variety of music genres. So I formed a band and did all genres of music, such as songs for idol stars, heavy metal, noise music, jazz, funk, and so on systematically, not specializing in uchikomi-type synthesized music. When we decided to do jazz next, for example, we would listen to a lot of jazz CDs to learn from them and then put their essence into our work. We intended to have people enjoy our ideas and arrangements as producer-musicians as a band, rather than showing off our singing or playing skills. I listened to every genre of music and arranged music following its style. I think I trained a lot through those activities during this period. But I did not delve deeply into a single interest. Because of this, I had a hard time in later years (laughs).

I’ve heard that you made music for an independent film when in university.

KOSAKI: YAMAMOTO Yutaka, who is currently active as a film and animation director, is an old friend of mine. We were classmates at high school and went to the same university. When the animation circle he belonged to made an independent film, I was asked to make music for it. It’s Onnen Sentai Ressentiment (Grudge squadron Ressentiment) (1997, planned, directed, and edited by YAMAMOTO Yutaka). For some reason, they even made me play the role of an evil leader. I’m really embarrassed about it now (laughs). The film has a complicated nature. It is a parody of Aikoku Sentai Dai Nippon (Patriot squadron Great Japan) (1982, director: AKAI Takami, mechanical design: ANNO Hideaki, and production: DAICON FILM), which is an amateur tokusatsu film and itself a parody of the Super Sentai tokusatsu series by Toei Company, Ltd. I think that was my first incidental music for a video work.

Around that time, to make music, I each time listened to existing music pieces first and imitated their styles. I decided on a music genre and then incorporated its characteristic expressions, such as tones and chords. As I had no formal music education, my ability to imitate was not so high. I rarely use music paper. I just write part scores to convey to the band members how and what to play before playing live. In fact, I’ve never composed music on music paper. When I was in university, I worked part-time to get more and more equipment, such as Roland’s XP-50 synthesizer (released in 1995), AKAI’s S3000XL sampler (released in 1996), and Roland’s VS-880 digital MTR (released in 1996). In particular, having the S3000XL expanded the genres available for my music.

When I joined the composition circle, it already had senior and alumni members who had joined it in the last decade or so. Circle members published a demo tape of their works once a month, and alumni members also participated in it, so I was able to interact with those members. I was inspired by some works of former members having full-time work, which were beyond the level of university students. We also published a newsletter that included our own reviews on the works in the demo tape. I learned a lot from reviews on my works.

KOSAKI says that he started composing music in a university circle.

KOSAKI says that he started composing music in a university circle.

Giving full attention to music as work

After graduating from university, you had a job at a game maker.

KOSAKI: I vaguely wanted to have a job related to music. In my job-hunting activities, I took employment exams at record companies and musical instrument manufacturers such as Yamaha Corporation and Roland Corporation. At job interviews, I gave a presentation on my idea for an automatic mastering function using artificial intelligence. At the time, they just laughed and said, “We don’t need such a thing.” In recent years, it has been becoming a hot new technology in the music industry. After 20 years, I say, in my mind, “I told you at that time!” (laughs). I eventually received a job offer from the game maker Namco Limited. I had submitted to the company a demo tape of my compositions from my university days. I had always liked the music of sound creator SANO Nobuyoshi (*1), who was in charge of the Ridge Racer series and the Tekken series of Namco, so I decided to work for Namco, hoping to work with him.

At Namco at that time, music composition was not separated from sound effects (SE) production, so I did everything related to sound in video games, including voice recording by voice actors and overall post production audio work (called multi-audio or MA in Japan). I was first assigned to creating the BGM for a puzzle game Aqua Rush (2000) as an on-the-job training. It was completely different from the music creation method that I knew. I had my hands full learning about development environments and how to incorporate music into video games. It was the period of transition from the conventional system of generating sounds by programming to the new system of streaming playback of recorded audio. The video game music industry was experiencing a great change. Since Aqua Rush still played sounds by the programming method, I composed its music by making a huge table of numbers using Excel spreadsheet. I had done similar work on the PC-9801 when I was in junior and senior high school, so the task itself was not so difficult for me.

The biggest difference in composing music at a university club and at a job is that music composed as a job needs to meet orders. I need to make sounds and music to meet specifications and requirements and deliver each work by the deadline. If it doesn’t meet the idea of the client, they will ask you to modify or simply reject it. How much you are confident in your proposal, it may be easily overturned by any perception gap between you and the client. I take it for granted now, but I experienced it for the first time at the time. I was also surprised by overwhelmingly high-quality works by my senior colleagues. For example, when making a techno-style song, the work by a senior colleague who knew better about techno was much cooler than mine. With my experience at university, I was confident of cleverly handling a variety of genres, but I realized again that I lacked sufficiently deep understanding for each genre and it was an obstacle for me. As I said earlier, the problem was caused by that I had not delved deeply into a single interest, that is, I had been involved in various genres of music widely but shallowly. From that point on, I started listening to all genres of music and studied them from scratch all over again. I’m ashamed to say this, but I listened to The Beatles very seriously for the first time at that time. I had thought that their music is a part of the artistic culture and is not on the same ground as my music. But as I listened to it more, I realized more that many things have their roots in the group’s music. I finally became aware of the historical connection of music around that time.

What are particularly memorable works with Namco for you?

KOSAKI: The most memorable work is the puzzle game Kotoba no Puzzle: Mojipittan (Word puzzle) (2001) as it is the first video game, I was responsible for everything. Although it is a puzzle game, I incorporated a lot of songs and Shibuya-kei (Shibuya-style) sounds into the work. When I listen to it again now, I feel I did what I wanted to do as I just wanted to do. As I just told you, I made the work during my intensive study period, I feel a naked part in my core was exposed in the work. I also meant that work to pay tribute to the good, old Namco sounds by reproducing the sounds of early Namco titles I had loved as a child, such as Pac-Man (1980), Mappy (1983), and Druaga no To (The Tower of Druaga) (1984), by tracing back to their waveforms by programmable sound generators (PSG, or electronic circuits for creating video game sounds) used around their time. Another memorable project was the music for the Tekken fighting game series. I first participated in the series from the Tekken Tag Tournament (1999), then worked on Tekken 4 (2001), Tekken 5 (2004), and up to Tekken Dark Resurrection (2006). I was involved in the series for a long period of time. The series much used relatively hard techno, breakbeats, and rock crossover (called “mixture rock” in Japan). They were not my fortes, to be honest. But I learned from SANO Nobuyoshi and other experienced colleagues how to create music in such genres while maintaining their qualities.

I’m not the type of composer who creates melodies as if suddenly falling down from the heaven into their mind. I start with conceiving a comprehensive framework, such as an overall sound image, genre, and scenes to express and matching sounds. I am also very particular about melodies, so even if I feel a certain melody is not special and boring at first, I improve it through trials and errors spending time. First, I create a melody by humming while playing the piano, record it as data in the sequencer, and then tweak it note by note, while asking to myself, “Should I raise or lower here?” until eliminating any odd parts and modifying mediocre parts. I spend much time doing the process. So I think I could not have become a professional composer without DTM, the tool that can create music while simulating various possibilities. I’m envious of people who are able to suddenly come up with melodies and compose music on music paper. I think I’m an opposite type of composer to TANAKA Kohei (*2), who was featured in this series in the previous time (laughs).

KOSAKI said: “I’m not the type of composer who creates melodies as if suddenly falling down from the heaven in their mind.”

KOSAKI said: “I’m not the type of composer who creates melodies as if suddenly falling down from the heaven in their mind.”

First animation involved as a freelance became a big hit

You left Namco in 2005 and became freelance. Why did you make the decision?

KOSAKI: I more and more wanted to do something challenging outside my workplace and seeking other possibilities for myself. To tell the truth, while still working for Namco, I had entered competitions for works for Japanese pop music artists, and failed in all of them (laughs). Eventually, YAMAMOTO Yutaka, who was with Kyoto Animation Co., Ltd. at the time, asked me to make the music for the original video animation (OVA) work MUNTO Toki no Kabe wo Koete (Munto: Beyond the Walls of Time) (2005). Around the time, OKABE Keiichi (*3), who was my boss at Namco, established the music production company MONACA Inc., and asked me to work with him. So I left Namco and joined MONACA to start working freelance.

Right afterward, you worked on the great hit TV animation Suzumiya Haruhi no Yuutsu (The Melancholy of Haruhi Suzumiya) (2006).

KOSAKI: Right. I was very surprised that I had such a big hit as soon as I became freelance. Even though I’d had worked with YAMAMOTO and Kyoto Animation before, I was still a new face with little experience. I’m still grateful they chose me. I think this work was a great leap for Kyoto Animation, too. I was very pleased to be able to join the work. At the time, I just simply worked hard to do what I was able to do.

I was basically in charge of the incidental music. As there would be several insert songs, I naturally worked on them. One of them, God knows..., became a big hit unexpectedly, ranking fifth on the Oricon weekly singles chart. I appreciate Kyoto Animation people’s careful drawing of the band’s performance scene. It was also amazing that the record company in charge decided and prepared to release its CD as soon as the episode with the song was broadcast on TV. As I said, this kind of band sound was totally an unfamiliar genre for me. I needed to study very hard to write God knows.... What is more, it was the first experience for me to ask musicians to come to the studio to record in a band format. I even didn’t know much about how to write the parts for the recording. Honestly, I was very nervous (laughs).

About God knows..., many people may feel its guitar performance is impressive. I can’t play the guitar, and guitar sound is the most difficult to express by uchikomi programming as it doesn’t have a good affinity with DTM. I often have no idea about how the finished work will be like until I hear the guitarist play it in the studio. For God knows..., I employed the guitarist, NISHIKAWA Susumu, and said to him: “It’s for an alien high school girl named NAGATO to play, so make it a cool, very technically demanding phrase.” He understood my brief explanation and quickly created and played the intro phrase on the spot. It was amazing. We had only three musicians, NISHIKAWA with the bassist TANEDA Takeshi and the drummer ODAWARA Yutaka. Their performances stood out to each other and there was no surplus sound. An ideal balance required for good band sounds was achieved instantly. I was speechless in the corner of the studio, while watching their prompt work and enormous power (laughs).

It is important for players of the wind and string instruments to play exactly as written on the sheet music. On the other hand, we expect the rhythm section, such as electric guitar, electric bass and drums, to exert their unique musical characteristics as much as possible. They know how to do it. I’d never experienced drastically enhancing the perfection level of a work of mine in the studio with the help of musicians that much. So the recording was really exciting for me. This work changed my life in every sense.

(notes)

*1

SANO Nobuyoshi is a game music composer and former sound creator for Namco. He is current president of DETUNE Ltd. He is also active under the names SANO Denji and sanodg.

*2

TANAKA Kohei is a composer who has created music for many animation and video games. His representative works include music for the video game Sakura Taisen (Sakura Wars) (1996), the animation ONE PIECE (1999 –), and the opening theme song JoJo: Sono Chi no Sadame (JoJo: His Blood Destiny) for the animation JoJo no Kimyo na Boken (JoJo’s Bizarre Adventure) (2012). For details, please refer to Pursuing new sounds: Creators of music as media arts No. 1: TANAKA Kohei, composer (Part 1).

https://mediag.bunka.go.jp/article/article-18563/

*3

OKABE Keiichi is a composer, producer, and former sound creator at Namco. He established MONACA Inc. in 2004. His representative works include the video game series Tekken, the video game series Taiko no Tatsujin, the animation series Working!! and the animation series Yuki Yuna wa Yusha de Aru (Yuki Yuna is a Hero), and the video game series NieR.

KOSAKI Satoru

Composer, arranger, and producer, born in Osaka Prefecture. After graduating from the School of Information Science, Faculty of Engineering, Kyoto University, he worked for Namco Limited (currently Bandai Namco Studios Inc.), before joining MONACA Inc. in the fall of 2005.

http://www.monaca.jp/member/

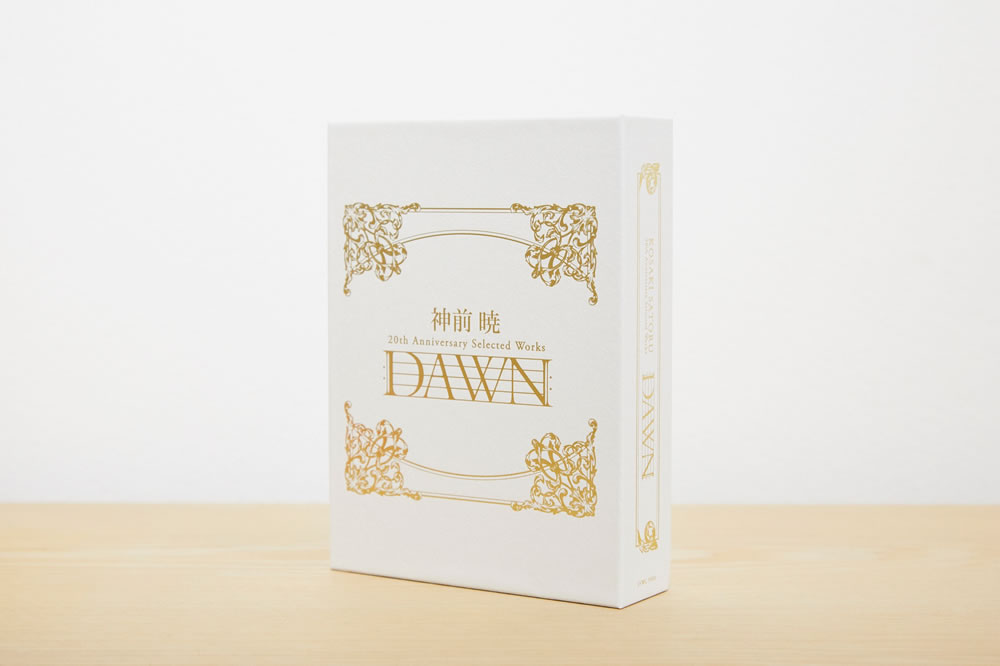

In March 2020, in commemoration of the 20th anniversary of his debut as a composer, KOSAKI SATORU 20th Anniversary Selected Works DAWN was released. The photo shows the limited edition (¥7,000 plus tax), which consists of a total of five discs of songs and incidental music. The standard edition (¥3,900 plus tax) consists of three discs of songs.

In March 2020, in commemoration of the 20th anniversary of his debut as a composer, KOSAKI SATORU 20th Anniversary Selected Works DAWN was released. The photo shows the limited edition (¥7,000 plus tax), which consists of a total of five discs of songs and incidental music. The standard edition (¥3,900 plus tax) consists of three discs of songs.

https://kosakisatoru-20th-anniversary.com/

*URL links were confirmed on June 16, 2021.