Composer KOSAKI Satoru has led the world of animation songs and animation incidental music in the 2000s and 2010s. The first part of this interview features his experiences with music in his childhood and school days, and his work as a composer for a game maker. This second part focuses on his activities after he became freelance, including his music for great hit animation series such as Suzumiya Haruhi no Yuutsu (The Melancholy of Haruhi Suzumiya) and Laki☆Suta (Lucky Star), and his thoughts on and ideas for his music creation and the future of the industry.

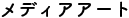

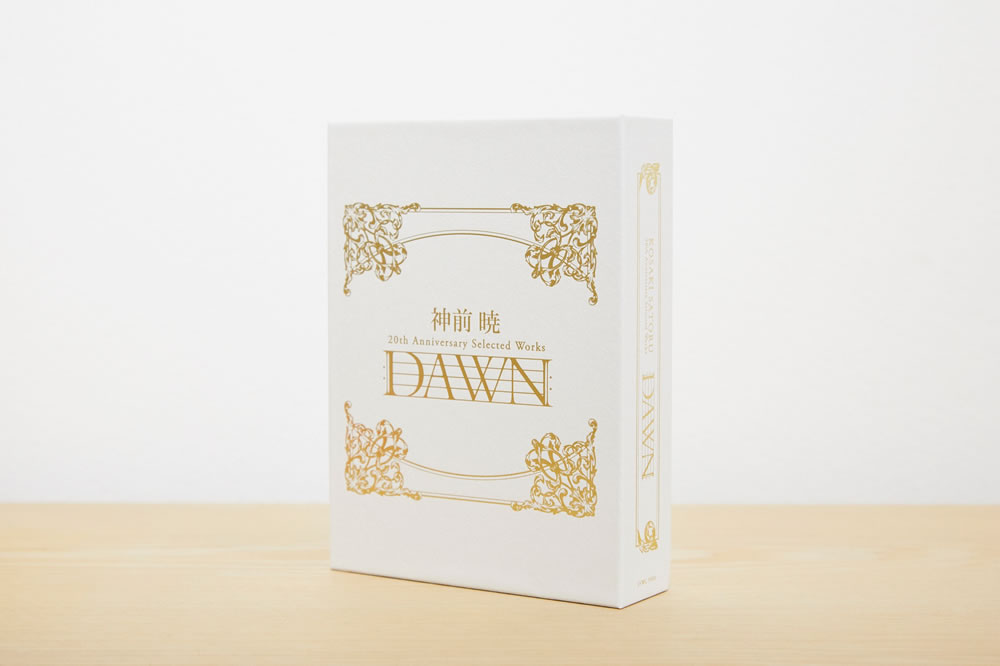

In commemoration of the 20th anniversary of his debut as a composer, KOSAKI SATORU 20th Anniversary Selected Works DAWN was released.

In commemoration of the 20th anniversary of his debut as a composer, KOSAKI SATORU 20th Anniversary Selected Works DAWN was released.

Photos: HATAKENAKA Aya (all photos in this article)

Creation of popular theme songs and their backgroaund stories

Following the TV animation Suzumiya Haruhi no Yuutsu (The Melancholy of Haruhi Suzumiya) (2006), Laki☆Suta (Lucky Star) (2007) also became a big hit.

KOSAKI: Laki☆Suta (Lucky Star) was the next work of Kyoto Animation Co., Ltd., and the staff was almost the same as for Haruhi, so I was asked to join again. Unlike in the previous work, I was assigned to make the theme song, too, and I became more responsible. To my surprise, the requirements for the theme song were relatively vague. I was told to “make a song that has not been heard before,” “incorporate rap,” and “set the tempo at 150 bpm to meet the number of frames depicting dance scenes.” I remember they showed me a Glico Pocky’s advertisement with actress ARAGAKI Yui as reference material. The bottleneck was the request for “a song that has not been heard before.” We made a lot of discussions when making a demo. In the beginning, I made it in British rock style like The Who or Blur, or in rock crossover (called “mixture rock” in Japan) style like YKZ. In the end, I got a little desperate and sent them a demo with many phrases with cut-up and loops evoking the feeling of much edited with dubs. Then, they told me, “Interesting!” Combining HATA Aki’s moe rap lyrics with the music caused metamorphosis like a sudden chemical reaction to create an explosively powerful song. The metamorphosis was so drastic that I feel there have been very few works that could follow this song so far, by my own creation or in other animation. I also feel all people involved in this work became playful and even a little mischievous all together to gain momentum of creating something interesting..., including myself, HATA Aki, voice actors singing it, and the drawing staff of Kyoto Animation. That environment was the source of creating the extraordinary, unique song, Motteke! Sailor Fuku (Take it! sailor suit-style school uniform for girls).

Around the time was the dawn of online video sharing sites. The release of the song coincided with the explosively growing popularity of posting Odottemita (We/I danced) videos. As with Hare Hare Yukai (Haruhi dance) of Haruhi, it was YAMAMOTO Yutaka’s idea to combine a dance with a theme song, I think. He is a very talented trend-setter, with prompting secondary creations like this.

In 2009, your life’s work, the animation series Monogatari, started.

KOSAKI: In the first work, Bakemonogatari (Ghostory) (2009), I was in charge of everything except the ending theme, which was done by supercell. The story is structured with blocks, each focusing on each of the five heroines. I was asked to create a different opening theme for each heroine to sing. Thinking calmly, I felt it a little outrageous as it means to frequently change theme songs during the course of one season (13 episodes) (laughs). In fact, the schedule was quite tight, both for creating the music and the opening animation, but we managed to overcome. I think the animation production studio Shaft in charge had a hard time to make the high-quality animation.

One of the opening themes, Ren-ai Circulation, was sung by voice actress HANAZAWA Kana. It was used again later in the NHK E-TV child-rearing program Sukusuku Kosodate, and more recently ranked first on the weekly ranking on the short-form video site TikTok. I’m pleased this song is loved by so many people for such a long period of time. When making its music, I thought it must be very interesting if HANAZAWA, with her cute voice, sings a non-aggressive, artistic and cultural, Japanese-language rap song, as artist Kaseki Cider did in the 1990s’ Shibuya-kei music. In this respect, I created this work as if reviving a good, old song. Later, it was accepted as a new song by a generation who did not know the animation when it was broadcast. I feel the phenomenon is very interesting. I’ve experienced such a thing for the first time in my career over more than 20 years.

About the incidental music to accompany the animation, the music selector did an excellent job such that the music sounds as if I composed each piece to meet each scene of the finished animation. But in reality, for the first season of the animation, I composed and stored all pieces in advance [to be selected appropriately for various scenes by a music selector]. The latter method is common in TV animation. From the sequel second season, I also used the former method. There is no series other than the Monogatari series that I have been involved in so deeply for such a long period of time.

How has the Shibuya-kei pop music in the early 1990s, which you just talked about, influenced your music creation and style?

KOSAKI: It’s very important for me. I’m a little younger than the generation who listened to the music just in real time, and I listened to it later when I was in university. I was astonished by its musicians’ outstanding sense of sound. I was also able to experience various types of Western pop music that they used as their source material, so I was greatly influenced by them. Even now, when I listen to their music, I feel that its quality is really high. It was very enjoyable to find out what types of pop music they listened to and where and how they used elements of the music in their music. It was just like the creators and the listeners playing a fun game together. I also think this is a very smart music education method. It was quite natural that creators of a slightly younger generation, such as myself and KITAGAWA Katsutoshi, were greatly influenced and incorporate its essence into our works. But at the same time, I am always worried that using styles of senior musicians in my works may be perceived as a professional composer’s typical attention-getting, unabashed approach. For me, it is very natural that my favorite music that I listened to a lot when I was an adolescent is deeply embedded in me and comes out from time to time (laughs).

Is there any difference between the composition process for theme songs, insert songs and character songs, and the composition process for incidental music, that is, BGM?

KOSAKI: Unlike theme songs, incidental music should be positioned as a part of animation, similar to its background art, I think. Having a different touch, for example, whether its background art is realistic like a photo or attractively deformed, makes a great difference in the animation’s overall atmosphere. I believe that incidental music plays a role in determining the colors of the work in a way. I have the mindset of working on the music part of the overall animation production, rather than concentrating on creating incidental music. On the other hand, a theme song is the face of each work. It is required to be powerful, melodious, assertive, and easy to remember. Incidental music should not be too assertive, and in some works, I need to make it less melodious and carefully limit the number of melodies to use. I think it’s cool if I can attract the audience to the texture of my incidental music by carefully selecting its musical instruments and tones.

These days, theme songs are often decided by auditions or competitions led by record companies. Thankfully, more often than before, I’ve been asked to in charge of both theme songs and incidental music for the same work. It means the composer needs to bear really heavy responsibility. For example, if the theme song and the incidental music share the same melody, when one of them is not as good as expected, there is no way to replace it. I understand well that the production side wants to use different composers for the theme song and the incidental music as a risk management measure. Nevertheless, my ideal is to contribute to each work by producing the best results in both of them. I’m very happy if they are aware of my ideal and entrust me with their works.

KOSAKI said: “A theme song is the face of each work. I think it is the reason why every theme song is required to be powerful, melodious, assertive, and easy to remember.”

KOSAKI said: “A theme song is the face of each work. I think it is the reason why every theme song is required to be powerful, melodious, assertive, and easy to remember.”

The 2017 animation film Uchiage Hanabi, Shita Kara Miru ka? Yoko Kara Miru ka? (Fireworks, Should We See It from the Side or the Bottom?) also attracted a lot of attention.

KOSAKI: The film is based on the live-action TV drama by director IWAI Shunji, Uchiage Hanabi, Shita Kara Miru ka? Yoko Kara Miru ka? (Fireworks, Should We See It from the Side or the Bottom?) (1993). I liked the drama very much. I watched it in real time during a depressing summer vacation when I was a ronin student (preparing for university entrance exams after failing them). I have fond memories of the drama. When I was asked to write the music for the animation film version, I wanted to create something that could be as good as film music, by taking a cinematic, Japanese film-like approach, rather than animation music. I like slightly “moist” music of many Japanese films, so I wanted to pay homage to those films as well.

I used many piano sounds throughout the work. I also used a lot of string and wind instruments. Shortly before I became in charge of this animation, I took a break from work due to health problems. During that time, I studied music theory from the basics, such as harmony and counterpoint, under a teacher at a music college. I’d always had an inferiority complex about not having a formal musical education. After studying, I felt much more positive about myself. I think I was able to put the results of my study into the music of the animation film Kizumonogatari (Wound story) (2016–2017) and Uchiage Hanabi, Shita Kara Miru ka? Yoko Kara Miru ka? (Fireworks, Should We See It from the Side or the Bottom?). At the same time, once that I became able to take a classical music-like approach a little, I more clearly acknowledged the high level of skills of orchestrators (orchestral music arrangers), who are specialists in the field. I’d dedicated my time to studying the music for songs and melodies over the past 20 years, while they’d dedicated almost the same amount of time to studying and doing orchestration. I’m no match for them in the field. So I did not hesitate to ask orchestrators to work on some of the pieces. In a word, I became able to ask for their cooperation candidly.

Various CDs of theme songs and soundtracks KOSAKI created for video games and animation works

Various CDs of theme songs and soundtracks KOSAKI created for video games and animation works

Composing music while keeping an objective point of view

Are there any music creators you look up to or who are a source of inspiration for you?

KOSAKI: TANAKA Kohei, who created music for Top wo Nerae! (Gunbuster! aka Aim for the Top!) (1988), SAGISU Shiro (*1) of Fushigi no Umi no Nadia (Nadia: The Secret of Blue Water) (1990), and KANNO Yoko (*2) of Macross Plus (1994). I have been greatly inspired by these works and these creators. When I was a child or a student, I was enthralled by the music by various creators, with the three at the top of them. It’s amazing that those creators are still active now, and even remain on the front lines. I want to be like them, but they are actually a high wall I can never climb over (laughs). When I wrote the music for a theme song for the animation Sekirei (2008), I made it sound like paying homage to TANAKA Kohei’s compositional style. Right after that, he gave me a phone call, even though we hadn’t been acquainted with each other. I went to see him with anxiety, being certain I would be scolded by him. To my surprise, he liked it and said, “Your music is very good!” (laughs).

I made my debut as a composer later than composers of my age, such as YAMASHITA Kosuke (*3) and IZUTSU Akio (*4). Their careers are longer than mine and advanced by one rank or even two. Incidental music composers with similar careers to mine are, for example, SAWANO Hiroyuki (*5), YOKOYAMA Masaru (*6), KANNO Yugo (*7), SUEHIRO Kenichiro (*8), and HAYASHI Yuki (*9). Incidental music composers of the generation are many and diverse. Composers of the music for songs include OISHI Masayoshi (*10) and TABUCHI Tomoya (*11). We are all good friends with each other and drink together. I am a fan of them and stimulated by them. Also, they are my rivals. When I hear their good music, I feel I’m defeated.

How do you feel about the younger generation of music creators?

KOSAKI: The vocaloid generation is already at the forefront of the music industry, such as YONEZU Kenshi as a leading artist among them, and the bands liked by the so-called “yakosei” listeners (night-loving listeners, deriving from the fact that those bands are associated with the word night). About animation song-oriented musicians, ryo of supercell (*12) and kz of livetune (*13) are already veterans. When including Official Hige Dandism and FUJII Kaze, I’ve never seen such a rich lineup of Japanese pop music artists since the Shibuya-kei music in the early 1990s. I think that the era of strategic Japanese pop music led by big-name producers has taken a break, and a wide array of characteristic individual artists has started to emerge instead. With the spread of the Internet, the opportunities to present and see creative works have increased dramatically. In a good sense, the barrier between professionals and amateurs has become much lower.

I have roots in a dojin music/DTM. I feel that the vocaloid generation uses a different creation method from mine. Typical is using vocaloid. They view vocals as a kind of music instrument. Their melody lines are complex, and their approach to chords and tones is really free. When we make music, even with the uchikomi method, we are always asking ourselves, “Is it possible for human to actually sing/perform this melody?” We are bound with that way of thinking. In contrast, they are free from the limiter and many other things that may block their activities.

The situation in the world of incidental music is a little different. It’s not easy for young composers to get work right away. Having a reliable relationship is essential to entrust a composer with the work of making dozens of music pieces with no anxiety. I think the long-time collaboration between, for example, ANNO Hideaki and SAGISU Shiro, or OSHII Mamoru and KAWAI Kenji (*14), cannot be realized without an established teamwork system and a strong relationship of trust.

What is important for you, that is, you work policy, when you compose music?

KOSAKI: I always want to keep an objective perspective of how the listener will feel about my music. Composer’s work tends to be very self-centered, and when it happens, it will not be successful as business. Of course, as I mentioned earlier, I add my own color to my work and I also want to do what I want to do, but it is still important to see things from the client’s point of view. It is not interesting if I just follow the order and make and deliver what the client expects me to do, so I make efforts to go a little off their assumption..., especially when I make the music for songs.

About the music for songs, I usually use the “tune-first” method, in which I create a melody first and then have a lyricist add lyrics to it appropriately. As long as I remember, I have written only a few songs using the “lyrics-first” method. But I’m actually better at the lyrics-first method (laughs). It’s easier for me to create a melody after appreciating the sounds of the lyrics and the world view of the story depicted in the lyrics. Unfortunately, in the current animation industry, tunes are made first for most songs. I heard that TANAKA Kohei writes much of his music with the “lyrics-first” method. I have no idea why he can do so (laughs).

Thoughts on the future of music for animation and video games

Do you have any suggestions for the future of the animation and video game industries as a watcher of the industries for the last 20 years?

KOSAKI: Several very talented young composers have emerged in the field of the music for songs. I think that more and more will emerge from the digital native generation. This has something to do with what I said earlier, but when I look at the array of characteristic Japanese pop music artists, the world of animation songs is not allowed to sit back and remain unchanged, I think. I also feel that music media will continue shifting from CDs to distribution and subscription. In fact, distributed music has already become much easier to listen to. What’s more, it is possible for listeners to access subscribed music sites with their smartphones and create their own playlists to enjoy music more. If you hear a music piece on the street and feel it interesting, you can use a music recognition app to catch and listen to it right away... It is absolutely right for listeners to be exposed to unknown music in that way.

As a music creator, I want to continue the culture of packaging objects such as CDs. I also feel the biggest problem with music distribution and subscription is that credits are not listed properly. We should know who made the music and who is playing, and it can lead you to have an interest in more music. Actually, I often buy CDs just to know that. Neglecting that matter and distributing only sound sources are not a welcome trend for the future of music. It’s really strange that we can get less information than we did in the analog record era, even though we live in the society where so many advanced information devices are present.

Let us hear some advice for the next generation of animation and game music creators who will follow in your footsteps.

KOSAKI: The most important thing is to listen to music. Regardless of whether or not you are a creator or aim to be a creator, you should aim to be a top-notch listener first. If you don’t have a good sense of listening, you won’t be able to have drawers in your mind to store various music and knowledge, and you won’t be able to judge the quality of your own work. As I just said, we live in an age where we can listen to any kind of music in the world with just a single smartphone, so I suggest you listen to as much music as you can and develop a solid ear.

I have one more thing. Although the advent of DTM and vocaloid has lowered the hurdles to creating music, the traditional academic field, including music theory, still means a lot. It is a discipline that systematically clarifies the human senses and their functions in relation to sound and music, and I think music creators should have the knowledge. Many creators naturally acquire the knowledge, but I strongly believe that you can acquire it faster by studying it. If you have any doubts about your music creation, I recommend you study it first. It doesn’t take so long. I say so based on my own experience.

My point is, the hurdles to making music have been lowered, but the music world is as wide and deep as it used to be. In order to find and secure your place in the music world, you should listen to music and study properly.

“I suggest that young creators aim to become top-notch listeners of music, first of all,” KOSAKI said.

“I suggest that young creators aim to become top-notch listeners of music, first of all,” KOSAKI said.

Thank you very much for your time today. Lastly, tell us about your plan for music creation in the future.

KOSAKI: It’s been almost 20 years since I worked on video game music. The situation of video games and their music has changed a lot. But I feel the change interesting. Recently, I worked on a Chinese app game. If I have a chance, I want to work on video game music once again. As another goal, I want to work on the music for live-action movies. Its world is deep and involves different approaches from animation music. I also want to create the music for an NHK serial morning drama and further an NHK taiga serial historical drama. This is the path that many senior and rival composers have taken, and I want to do it myself. I’m aware I must bear great responsibility. I also must overcome gastric perforation [to be caused by the resulting mental stress] (laughs).

(notes)

*1

SAGISU Shiro is a composer, arranger, and producer, born in 1957. SAGISU has been active in a wide range of musical fields since the 1970s, including fusion, pop, idol star songs, animation songs, and incidental music. His representative works include songs for such singers as KOIZUMI Kyoko, KAWAI Naoko, NAKAMORI Akina, and Misia; and music for the animation Fushigi no Umi no Nadia (Nadia: The Secret of Blue Water) (1990 –1991), and the animation series Evangelion Shin-Gekijoban (Rebuild of Evangelion).

*2

KANNO Yoko is a composer, arranger, and producer, born in 1963. KANNO made her debut as a professional composer in 1985 with music for the PC game Sangokushi (Romance of the Three Kingdoms). Around the same time, she also played keyboard as a member of the rock band Tetsu 100%. Her representative works include the animation Cowboy Bebop (1998), the animation Kokaku Kidotai: Stand Alone Complex (Ghost in the Shell: Stand Alone Complex) (2002 –2003), and the animation Macross F (Macross Frontier) (2008).

*3

YAMASHITA Kosuke is a composer and arranger, born in 1974. YAMASHITA studied under HANEDA Kentaro at Tokyo College of Music. He has created music for a variety of video works, including live-action films, video games, animation, and tokusatsu (special effects) works. His representative works include the movie Tenkosei: Sayonara, Anata (Switching: Goodbye Me) (2007), the video game series Nobunaga no Yabo (Nobunaga’s Ambition), the tokusatsu work Kaizoku Sentai Gokaiger the Movie: Soratobu Yureisen (Kaizoku Sentai Gokaiger the Movie: The Flying Ghost Ship) (2011), and the animation series Chihayafuru.

*4

IZUTSU Akio is a composer and musician, born in 1977. While working as a solo overdubbing unit Fab Cushion, IZUTSU has also composed music for advertisements and incidental music. His representative works include the drama Kaibutsu-kun (2010), the drama Tokusatsu Gagaga (2019), and the animation series Phi Brain: Kami no Puzzle (Phi Brain: Puzzle of God).

*5

SAWANO Hiroyuki is a composer, arranger, and lyricist, born in 1980. SAWANO mainly composes incidental music for dramas, animation, and movies, and also creates music for artists. His representative works include the drama series Iryu: Team Medical Dragon, the film and animation series Shingeki no Kyojin (Attack on Titan), the animation Kill la Kill (2013–2014), and the movie Mobile Suit Gundam: Senko no Hathaway (Mobile Suit Gundam: Hathaway’s Flash) (2021).

*6

YOKOYAMA Masaru is a composer and arranger, born in 1982. YOKOYAMA began to be active as a professional composer while still a student at Kunitachi College of Music. His representative works include the movie series Chihayafuru, the movie AI Hokai (AI Amok) (2020), the animation series Arakawa Under the Bridge, the animation series Mobile Suit Gundam: Tekketsu no Orphans (Mobile Suit Gundam: Iron-Blooded Orphans) (2015–2017), and the drama Warotenka (Laugh It Up!) (2017).

*7

KANNO Yugo is a composer and producer, born in 1977. KANNO has created music for movies, advertisements, and artists since he was a student at Tokyo College of Music. His representative works include the drama series Nazotoki wa Dinner no Ato de (The After-Dinner Mysteries) (2011), the taiga serial historical drama Gunshi Kanbei (Strategist Kanbei (2014), the serial morning drama Hanbun, Aoi. (Half blue) (2018), and the animation Gundam: G no Reconguista (Gundam Reconguista in G) (2014–2015), and the animation JoJo no Kimyo na Boken: Diamond wa Kudakenai (JoJo’s Bizarre Adventure Part 4: Diamond is Unbreakable) (2016).

*8

SUEHIRO Kenichiro is a composer and arranger, born in 1980. SUEHIRO has been active in bands since he was in his teens. He studied compositional techniques and orchestration under IWASHIRO Taro and OSAWA Akinori. His representative works include the drama series Yamikin Ushijima-kun (Ushijima the Loan Shark), the drama Nigeru wa Haji daga Yaku ni Tatsu (The Full-Time Wife Escapist) (2016), the animation series Golden Kamuy and the animation series En En no Shobotai (Fire Force). He often collaborates with MAYUKO and KAMISAKA Kyosuke.

*9

HAYASHI Yuki is a composer and arranger, born in 1980. HAYASHI is a former athlete for Men’s Rhythmic Gymnastics. He started his composer’s career by creating accompanying music for rhythmic gymnastics. His representative works include the drama series Doctors: Saikyo no Meii (Doctors: The Ultimate Surgeon), the serial morning drama Asa ga Kita (Asa has come) (2015), the movie Boku dake ga Inai Machi (Erased) (2016), the animation Kirakira☆Precure a la Mode (Kirakira Pretty Cure a la Mode) (2017) and the animation Boku no Hero Academia (My Hero Academia) (2016–2017).

*10

OISHI Masayoshi is a singer-songwriter and composer, born in 1980. OISHI made his major label debut with the band Sound Schedule in 2001. After it disbanded, he has been active under the names OISHI Masayoshi as a solo artist, and OISHIMASAYOSHI as an artist for animation and video games. His representative works include the opening theme song Yokoso Japari Park e (Welcome to Japari Park) (lyrics, composition, and arrangement) for the animation Kemono Friends (2017), and the opening theme song Union (lyrics, composition, and singing) for the animation SSSS.Gridman (2018).

*11

TABUCHI Tomoya is a lyricist, composer, and bassist, born in 1985. TABUCHI made his major label debut in 2008 with the band Unison Square Garden and has also created music for many animation and voice actors. TABUCHI has worked on many opening theme songs of animation as the band’s activities, including Orion wo Nazoru (Tracing Orion) (lyrics and composition) for Tiger & Bunny (2011), Sakura no Ato (all quartets lead to the?) (lyrics and composition) for Yozakura Quartet: Hananouta (Yozakura Quartet) (2013), and fake town baby (lyrics and composition) for Kekkai Sensen (Blood Blockade Battlefront) (2015).

*12

The group of creators, supercell, is led by ryo who has been releasing music on video sharing sites since around 2007. The group’s representative works include the ending theme song Kimi no Shiranai Monogatari (The story you don’t know) for the animation Bakemonogatari (Ghostory) (2009), the ending theme song Utakata Hanabi (Fleeting firework) for the animation Naruto: Shippuden (2010), and the opening theme song Giniro Hikosen (Silver airship) for the movie Nerawareta Gakuen (The Aimed School) (2012) (all lyrics, composition, and arrangement by ryo).

*13

The music unit, livetune, is led by kz who has been releasing music using the vocaloid Hatsune Miku on video sharing sites since around 2007. In 2008, the unit made its major label debut with Re:package from Victor Entertainment. The unit’s representative works include the opening theme song irony for Ore no Imoto ga Konnani Kawaii Wake ga Nai (aka Oreimo; My younger sister cannot be so pretty) (2010), the opening theme songs FLAT and Sen no Tsubasa (One thousand wings) for the animation Hamatora (2014), and the opening theme song All Over for the animation Maho Shojo Taisen (Magica Wars) (2014) (all lyrics, composition, and arrangement by kz).

*14

KAWAI Kenji is a composer and arranger. After playing in the fusion band Muse, KAWAI made his debut as an incidental music composer based at his home recording studio. His representative works include Mobile Police Patlabor the Movie (1989), Ghost in The Shell: Kokaku Kidotai (Ghost in The Shell) (1995), the video game Nobunaga no Yabo Online (Nobunaga’s Ambition Online) (2003), and Kamen Rider Build (2017).

KOSAKI Satoru

Composer, arranger, and producer, born in Osaka Prefecture. After graduating from the School of Information Science, Faculty of Engineering, Kyoto University, he worked for Namco Limited (currently Bandai Namco Studios Inc.), before joining MONACA Inc. in the fall of 2005.

http://www.monaca.jp/member/

In March 2020, in commemoration of the 20th anniversary of his debut as a composer, KOSAKI SATORU 20th Anniversary Selected Works DAWN was released. The photo shows the limited edition (¥7,000 plus tax), which consists of a total of five discs of songs and incidental music. The standard edition (¥3,900 plus tax) consists of three discs of songs.

In March 2020, in commemoration of the 20th anniversary of his debut as a composer, KOSAKI SATORU 20th Anniversary Selected Works DAWN was released. The photo shows the limited edition (¥7,000 plus tax), which consists of a total of five discs of songs and incidental music. The standard edition (¥3,900 plus tax) consists of three discs of songs.

https://kosakisatoru-20th-anniversary.com/

*URL links were confirmed on June 16, 2021.